In the framework of the European Ombudsman’s inquiry, opened following a complaint by European Democracy Consulting (EDC), the Authority for European Political Parties and European Political Foundations (APPF) provided its reply to the complaint. Upon proposal from the Ombudsman, European Democracy Consulting provided its comments of this reply.

On 26 June 2020, European Democracy Consulting lodged an official complaint to the Office of the European Ombudsman in relation to the failure of the Authority for European Political Parties and European Political Foundations (APPF) to implement its transparency requirements under EU Regulation 1141/2014 on the statute and funding of European political parties and European political foundations.

On 28 July, European Ombudsman Emily O’Reilly announced her decision to open an inquiry into the APPF’s compliance with its transparency obligations. The APPF was invited to provide a reply on the issues raised in the complaint, which it did on 5 October. In turn, European Democracy Consulting was invited to comment upon the APPF’s reply. Below are our comments (click here for the PDF report).

Introduction

Following the APPF’s reply of 5 October to the European Ombudsman’s letter, European Democracy Consulting is grateful for the opportunity to provide its assessment of the arguments brought forward by the APPF.

In order to help the reader’s understanding of this assessment, and avoid the need to juggle between documents, we are taking the liberty to include some context to our response.

The first part of this assessment therefore briefly recalls the legal obligations of the APPF arising from Article 32 of Regulation 1141/2014 on transparency, as well as the current online availability of this information. The second part directly addresses the arguments brought forward by the APPF. Each point follows a three-part structure, comprising a summary of our initial assessment, extracts from the reply of the APPF, and our assessment of this reply. Finally, a third section broadens the debate to the issues of transparency and clarity for EU institutions.

In her letter, the European Ombudsman added a concern for the use of European languages by the APPF’s website. While we support a more diverse use of languages in order to increase the availability of information to European citizens, we refrain here from addressing this issue, as it was not part of our initial assessment. Nevertheless, we look forward to the Ombudsman’s conclusions on this point as well.

As we have done from the beginning of this initiative, we wish to recall the constructive nature of this complaint, which takes good note of the limited size and funding of the APPF — a point emphasised by its Director in his reply. Our hope is for the Ombudsman to recognise the validity of our arguments and the shortcomings of the APPF’s current provision of information so that this decision may both strengthen citizens’ understanding of European parties and also be used to successfully increase the APPF’s resources to match its full obligations.

Context of the assessment

Review of transparency obligations

Pursuant to Articles 6, 7 and 32, the European Parliament is required to “make public, under the authority of its Authorising Officer or under that of the Authority, on a website created for that purpose” (Article 32(1)) a series of information. In layman’s terms, this information includes:

- the names and statutes of registered European political parties and foundations;

- the applications that have not been approved and the grounds for rejection;

- the documents submitted as part of applications for registration, whether the application has been approved or not;

- an annual report with amounts paid to each European political party and foundation;

- the annual financial statements and external audit reports of European political parties;

- the final reports on the implementation of the work programmes or actions of European political foundations;

- the names of donors and the value of donations for all donations reported by European political parties and foundations, for donations above €1,500 (if written consent was given, for donations above €1,500 and under €3,000);

- the number and sum of donations under €1,500 from natural persons and of donations above €1,500 and below €3,000 for which consent to publication was not given (bundled as “minor donations”);

- the contributions from legal entities members of European parties and foundations and the identity of the member parties or organisations which made those contributions;

- the details of and reasons for final decisions regarding sanctions taken by the Authority and the European Parliament;

- a description of the technical support provided to European parties;

- the evaluation report of the European Parliament on the application of this Regulation (starting in 2021); and

- an updated list of MEPs who are members of a European political party.

Additionally, the European Parliament is required to “make public the list of legal persons who are members of a European political party […] as well as the total number of individual members” (Article 32(2)).

Current online availability of required information

| APPF | EP | |

| the names and statutes of registered European political parties and foundations; | ✓ | ✗ |

| the applications that have not been approved and the grounds for rejection; | ✓ | ✗ |

| the documents submitted as part of applications for registration, whether the application has been approved or not; | ✓ | ✗ |

| an annual report with amounts paid to each European political party and foundation; | ✗ | ✓ |

| the annual financial statements and external audit reports of European political parties; | ✗ | ✓ (until 2017) |

| the final reports on the implementation of the work programmes or actions of European political foundations; | ✗ | ✗ |

| the names of donors and the value of donations for all donations reported by European political parties and foundations, for donations above €1,500 (if written consent was given, for donations above €1,500 and under €3,000); | ~ | ✗ |

| the number and sum of donations under €1,500 from natural persons and of donations above €1,500 and below €3,000 for which consent to publication was not given (bundled as “minor donations”); | ~ | ✗ |

| the contributions from legal entities members of European parties and foundations and the identity of the member parties or organisations which made those contributions; | ✗ | ✗ |

| the details of and reasons for final decisions regarding sanctions taken by the Authority and the European Parliament; | ~ | ✗ |

| a description of the technical support provided to European parties; | ✗ | ✓ (until 2018) |

| the evaluation report of the European Parliament on the application of this Regulation (starting in 2021); and | N/A | N/A |

| an updated list of MEPs who are members of a European political party. | ~ | ✗ |

We see that the required information is, at best, displayed on different websites and, often, provided only partially or in an incomplete manner.

Assessment of the APPF’s arguments

Dedicated website

Our initial assessment (summary)

Article 32(1) lists information (see table above) that “the European Parliament shall make public, under the authority of its Authorising Officer or under that of the Authority, on a website created for that purpose” (emphasis added).

While this last criteria is open to interpretation, and despite publishing some relevant information, the European Parliament’s website cannot be considered “created for that purpose”. By contrast, the website of the APPF’s website focuses exclusively on European political parties and European political foundations; it was created along with the APPF, whose work is exclusively on the European parties and foundations. In practice, this obligation can therefore, without a doubt, be understood to refer to the APPF’s website — which should therefore publish all the information listed.

The APPF’s response (April 8, extract)

The Authority shares the duties and responsibilities […] with the European Parliament. Therefore, [Article 32] needs to be read in conjunction with the provisions underlying the remits of each of the two entities. […] As a result, the Authority publishes the documents and information identified under points (a), (b), (e), (f), (g) and (k) of [Article 32(1)], while the European Parliament ensures publication of the other documents and information identified in that paragraph and in Article 32(2). Those publications take place within the web infrastructure of the European Parliament.

The APPF’s response (5 October, extract)

The Authority [explained] to the complainant which are the practical reasons why documents can be found on two separate websites […]. […]

The information on both websites complement each other and therefore avoid duplications and potential inaccuracies. […] The Authority’s website has not been created for the purpose of publishing documents possessed by the European Parliament. The purpose of the Authority’s website is to inform citizens and the public about the Authority’s activities and to publish documents possessed by the Authority and destined for the public.

An approach that would oblige the Authority […] to publish documents that are in the remit of the European Parliament and which the Authority does not even possess, is neither in compliance with said Article, nor would it be in the public interest. Not only would the Authority need to depend on the agreement of the European Parliament to publish documents in European Parliament’s possession, but also the Authority would be in no position to ensure that the information contained in those documents is correct and up to date. […]

The Authority [intends] to work with the IT services of the European Parliament to insert such a reference [to the website of the European Parliament] in 2021.

Our response

While we recognise the APPF’s argument that Regulation 1141/2014 places different legal obligations on the APPF and on the European Parliament, it fails to account for Article 32’s opening line,1 which clearly indicates the legislator’s intention that citizens find all the listed information on a single website. At no point does the Regulation indicate, or authorise, a distinction for publication based on each institution’s other legal responsibilities.

Furthermore, since transparency concerns must necessarily be considered from the point of view of the user (more on transparency in the last part of this document), the APPF’s “practical reasons why documents can be found on two separate websites” are not only not permitted by the Regulation, but run directly against its intent and citizens’ ease of access to information.

Since the European Parliament’s website is not “created [or designed] for that purpose” and since the creation of a wholly new and separate website would create the “duplications and potential inaccuracies” which the APPF wishes to avoid, the APPF’s own website is the only one that can be considered the natural repository of all the information listed in Article 32.1.

Parting, the APPF has two options: either obtain the relevant information and documents from the European Parliament, or request it directly from the relevant entities. In its reply, the APPF claims that it would then “depend on the agreement of the European Parliament to publish documents in European Parliament’s possession” and “be in no position to ensure that the information contained in those documents is correct and up to date.”

Firstly, bearing in mind that the Authority is “physically located in the European Parliament, which shall provide the Authority with the necessary offices and administrative support facilities” (Regulation 1141/2014, Article 6(4)), that “both websites are hosted on the IT infrastructure of the European Parliament and are provided and run by the IT services of the European Parliament.” (APPF reply), and that “the Authority and the Authorising Officer of the European Parliament shall share all information necessary for the execution of their respective responsibilities under this Regulation” (Article 6(9)), it remains unclear why obtaining information from the European Parliament is more complicated than obtaining it from third parties such as European political parties.

Secondly, the APPF does not explain its supposed reliance on the European Parliament since, according to Article 23(1), “European political parties and European political foundations shall submit to the Authority, with a copy to the Authorising Officer of the European Parliament […]: (a) their annual financial statements […], (b) an external audit report on the annual financial statements […]; and (c) the list of donors and contributors and their corresponding donations or contributions […].” Furthermore, “control of compliance by European political parties […] shall be exercised, in cooperation, by the Authority, by the Authorising Officer of the European Parliament and by the competent Member States.” (Article 24(1)) and “European political parties […] shall provide any information requested by the Authority, […] which is necessary for the purpose of carrying out the controls for which they are responsible under this Regulation.” Therefore, while some of these documents are indeed published by the European Parliament, they should also directly be provided to the APPF by European parties and foundations.

Accordingly, we reiterate that not only is the APPF’s website the “website created for that purpose”, where all required information is to be found, but argue that all the relevant information can and should be made available to the Authority by relevant stakeholders, lifting any reliance on the European Parliament which, at any rate, is required to comply.

Financial information

Our initial assessment (summary)

Financial information — whether the amounts of public funds granted to parties and foundations, parties’ financial statements and audit reports, and contributions from member entities — is not displayed by the APPF. For some of the information, the content displayed is incomplete and falls short of meeting the requirements of disclosure of Article 32(1).

For instance, donations above €12,000 are listed with the names of their donors. However, donations below €12,000 are only published if received within 6 months of the European election. By contrast, Article 32(1)(e) clearly requires the publication of all donations above €3,000, of donations between €1,500 and €3,000 for which prior written consent was given, and of “minor donations” as a single amount, along with the number of these donations.2

The APPF’s response (5 October, extract)

2019 was the first year ever in which the Authority reviewed the financial accounts of EU Parties and EU Foundations [on the budget year 2018]. Following that review the Authority started to publish the information on donations and contributions contained in those financial accounts […]. Currently the Authority is in the middle of the second annual exercise of that review which covers budget year 2019. […] The Authority is grateful for your comments and intends to take those into consideration […]. […]

Regarding the “donations prior to 2018”, the Authority notes that it was operationally set up on 1 January 2017 and was mandated to check donations and contributions received by EU Parties and EU Foundations from budget year 2018 onwards. The Authority therefore neither possesses information about donations prior to 2018 nor does it have a mandate to process and publish such donations. Donations prior to 2018 can be found in the audit reports of the respective parties and foundations at EU level on the website of the European Parliament.

Our response

The first issue relates to the APPF’s non publication of information on public funding and donations received by European parties and foundations prior to 2018. We take note of the set-up of the APPF in January 2017 and, indeed, Article 40, 40a and 41 confirm that the APPF, according to its reply, is “mandated to check donations and contributions received by EU Parties and EU Foundations from budget year 2018 onwards.”

However, our argument does not bear upon the APPF’s duty to carry out its compliance duties, but upon its role of informing citizens — a role we will address further in the section on transparency. In this light, and since the APPF is fully aware that relevant information is publicly available on the European Parliament’s website (dating as far back as 2008), nothing precludes the APPF from using this information to inform citizens.

The second issue relates to the APPF’s publication of donations which did not meet the requirements of Regulation 1141/2014. Beyond being grateful for comments, the APPF does not indicate the reason why it chose to publish donations in a way that differed from those prescribed by Article 32(1)(e), nor its intention to amend its reporting on 2018 donations to accurately meet its obligations. As such, we would like to underline that not amending the reporting on 2018 donations would make comparisons with 2019 donations impossible.

Sanctions

Our initial assessment (summary)

There is no page on the APPF website concerning sanctions, making it impossible to tell whether there has never been sanctions imposed, or whether sanctions are not displayed.

The APPF’s response (5 October, extract)

The Authority [appreciates] the point raised by the complainant and by the Ombudsman that under the current design of the Authority’s website there might be a potential doubt whether any sanctions have been imposed or not. The Authority therefore intends to work with the IT services of the European Parliament to insert a section on sanctions on the Authority’s website in 2021. In addition, the Authority will also assess whether other categories exist where the Authority does not yet possess any documents destined for publication but where an empty section should be added on its website in order to clarify that no such documents yet exist.

Our response

We are satisfied with the APPF’s commitment to act upon this recommendation, and commend them on pro-actively seeking other instances where an absence of information may lead to a lack of clarity.

List of MEPs

Our initial assessment (summary)

While the sections for each European party include documents indicating a list of their MEPs, there is no single consolidated list of MEPs with their affiliation (or lack thereof, should the list include all MEPs).

The APPF’s response (5 October, extract)

As regards the concrete example of a more harmonised “list of Members of the European Parliament who are members of an EU Party”, the Authority is considering proposing a template to EU Parties to be used when submitting updates to that list in the future.

Our response

While we commend the APPF on considering templates to harmonise the reporting of information by European parties, it is unclear what they would bring in this particular case and why the APPF seems unable to remedy this shortcoming right away. The publication of this consolidated list is a direct requirement arising from Article 32(1) and the APPF already possesses all the necessary information in the separate files provided by European parties. All that seems requires is the consolidation of this information into a single list.

For clarity, user-friendliness and completeness purposes, we strongly encourage the APPF to list all MEPs (thereby also indicating those MEPs who are not members of European parties) and to include supplementary information such as MEPs’ Member State, national party of affiliation (where applicable), and EU parliamentary group (or non-attached status). The European Parliament’s own list, which does not indicate European party membership, along with its search function can be useful models — especially since it appears the APPF’s website is actually “run by the IT services of the

European Parliament”, which should make the adaptation of this list easy.

Transparency and clarity

Beyond the specific points mentioned by the APPF in its reply, we would like to address the broader issue of transparency — the core concern of our initial complaint — and the obligations derived therefrom for EU institutions. We appreciate the opportunity given to us to expand upon this principle here.

What does it mean for EU institutions to be transparent? What does it entail for their work? Beyond strict and written obligations, are there requirements that EU institutions can sensibly be expected to meet?

Transparency principles in EU law

First are the rights of EU citizens. Beyond enshrining “democracy” as a founding value of the European Union, the Treaty on European Union (TEU) posits, in Article 10(3), that “every citizen shall have the right to participate in the democratic life of the Union.” The Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union, which now enjoys “the same legal value as the Treaties” (Article 6(1) TEU), mentions, in its Article 42 on the “right of access to documents”, that “any citizen of the Union […] has a right of access to documents of the institutions, bodies, offices and agencies of the Union, whatever their medium.”

Second are obligations on EU institutions. Article 10(3) TEU continues by saying that “decisions shall be taken as openly and as closely as possible to the citizen.” Article 11(1) goes on to require EU institutions, “by appropriate means, [to] give citizens and representative associations the opportunity to make known and publicly exchange their views in all areas of Union action.” And Article 11(2) details that “institutions shall maintain an open, transparent and regular dialogue with representative associations and civil society”. Likewise, in its “provisions having general application”, the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU), in Article 15(1) indicates that “in order to promote good governance and ensure the participation of civil society, the Union’s institutions, bodies, offices and agencies shall conduct their work as openly as possible.”

Read together, these provisions support a strong principle of transparency as part of the good public and democratic administration of EU institutions: information about the EU’s functioning must be made available to European citizens, and EU institutions have an obligation to make information available. As summarised by Sophie van Bijsterveld, Professor of Law, Religion and Society at Radbout University: “in order to be able to fully participate as a citizen or for the functioning of accountability mechanisms, transparency is crucial. Without transparency, the other principles fall short. In designing new mechanisms to secure good governance, all these elements must play a role.”3

The European Ombudsman herself has supported the importance of transparency writing that while “the EU has high transparency standards relative to many of the member states”, her task vis-a-vis EU institutions included “holding them to account when they sometimes fall short.”4 Indeed the Office of the Ombudsman’s strategy includes “[serving] European democracy by working with the institutions of the European Union to create a more effective, accountable, transparent and ethical administration” and “[encouraging] an internal culture of transparency, ethics, innovation and service to citizens.”

Transparency in practice

What does this need for transparency mean for the work of EU institutions?

While most of the emphasis rests on the idea of “right of access” to documents, the manner in which information is made public is an integral part of its transparency or lack thereof. A 2019 brief by the European Parliament for the PETI Committee on “transparency, integrity and accountability in the EU institutions” supports this view, writing that “transparency requires the disclosure of information on policy-making and spending, while ensuring citizens’ access to such information.”5 In order to implement their need for transparency, EU institutions therefore have the duty to ensure the information is accessible.

In The principle of transparency in EU law, Anoeska Buijze of Utrecht University details the idea of accessibility, writing that “transparency is always concerned with the availability, clarity, and intelligibility of information”6 and that “government should make information on its actions and performance available to outsiders, and should make it as easy as possible to observe what it is doing by using procedures that are clear, known, and simple”.7

This point is further emphasised by Professor van Bijsterveld who writes that “transparency, we must realise, is not simply concerned with providing (massive) information, but also with presenting it in a coherent and understandable fashion. […] Transparency is not simply concerned with information, but with useful information and a sensible ordering of the information. Meeting these requirements obviously places great responsibilities upon the authorities involved; but it is necessary to do so, and it is worth it. Quality of information and timely availability are important.”8

In essence, ensuring transparency is not limited to providing documents but includes making it easy for citizens to obtain the information they need. This principle is confirmed by the European Parliament’s Committee on Legal Affairs which emphasised, in 2015, that “reinforcing the legitimacy, accountability and effectiveness of the EU institutions […] is of the utmost importance” and that “rules of good administration of the EU are key to achieving this objective through the provision of swift, clear and visible answers in response to citizens’ concerns.”9

Institutions should therefore act pro-actively to provide citizens, not merely with information on their activities, but with concrete answers. This requires providing data and figures, but also relevant explanations and the necessary context and comparisons (with other items and with previous years) to understand this data.

Transparency concerning European political parties

The principle of transparency in European institutions is often discussed and applied with regards to EU institutions’ decision-making or law-making processes. However, there is no reason to limit the principles found in the treaties to these issues only.

In particular, Article 10(4) of the Treaty on European Union (the so-called “Party Article”) asserts that “Political parties at European level contribute to forming European political awareness and to expressing the will of citizens of the Union.” It follows that, in order to allow citizens to “participate in the democratic life of the Union”, citizens need to be provided with full transparency about European political parties, including the provision of swift, clear and visible answers regarding these political parties.

In the absence of other relevant institutions, such as a European electoral commission, the APPF is the only European institution whose mandate deals directly and exclusively with European political parties and foundations. Therefore, if obligations deriving from the need for transparency on European parties did not apply to the APPF, there would reasonably be no other EU institutions to which they could apply. This would leave European citizens with no source of information on publicly funded stakeholders essential to the forming of their political will, other than what these parties choose to divulge.

Ensuring transparency about European parties

Several times in its reply, the APPF seems reluctant to improve the full accessibility of information regarding European parties. For instance, it emphasises its limited staff and means, and had previously indicated that it was “not equipped to actively interact” with the public. While the APPF is certainly not to blame for its limited resources, this argument should not be used as an excuse not to meet legal obligations, but instead as an urgent point to address in order to meet these obligations in full.

With regards to the format in which its documents are published, it notes that “to its knowledge there is no requirement of a certain document format to be used”. While true, it surely has not escaped the APPF that PDF documents are never as easily machine-readable as Excel or Word formats, for instance, and that many of the documents it publishes simply do not allow for the copying of text. In particular, the electoral results provided by European parties are almost always screen captures or other images of entire electoral results from each country — resulting in non-copyable PDF documents of over 200 pages each. These simply cannot be considered as transparent information.

Indeed, this may be due to stakeholders providing requested information in non-readable formats, but the APPF could already have requested the submission of information in a different manner. More importantly, it could have taken it upon itself to turn this information (such as the MEPs of each European party, the 2019 electoral results, or donations) into machine-readable formats, with relevant graphs and figures — as we have.

The APPF further indicates that publishing the results of European elections by European party would “disregard the Authority’s legal obligation to publish the official results of the elections to the European Parliament”. However, it remains unclear why providing these results in a manner consistent with APPF’s object of work — in addition to the official results submitted by European parties — would be incompatible with EU law. At any rate, the way these results are provided falls far short of true accessibility providing answers to citizens’ question.

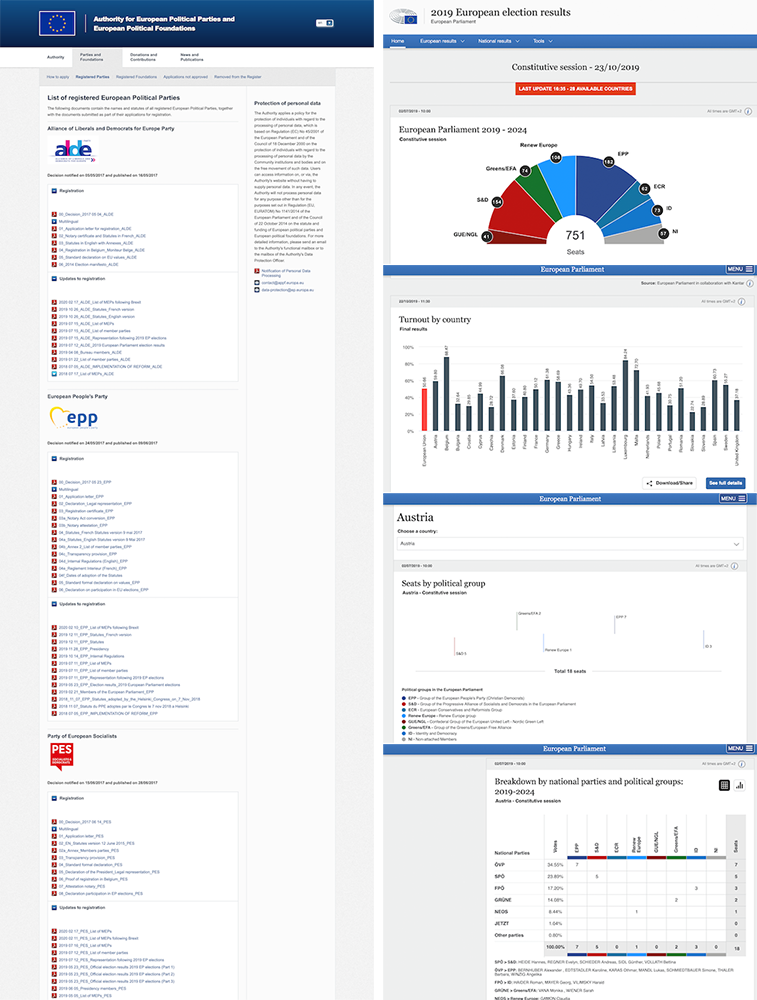

The pictures below compare the information on European parties provided by the APPF and information on parliamentary groups provided by the European Parliament, including a clear treatment of electoral results in order to make them understandable by citizens.

compared to

information on parliamentary provided by the European Parliament (right)

Finally, and more broadly, the APPF indicates that, in its view, “the purpose of [its] website is to inform citizens and the public about the Authority’s activities and to publish documents possessed by the Authority and destined for the public.” This activity-centred assessment falls short of a mission of transparency and public information, as required of European institutions.

Unfortunately, these responses match observations made by Professor Herwig Hofmann of the University of Luxembourg’s Centre for European Law and Professor Päivi Leino-Sandberg of the University of Helsinki. They observe that “too often, the institutional reaction has been to focus on ways how to restrict transparency as a bureaucratic nuisance. […] The EU institutions too often display a lack of understanding of the fundamental nature of transparency by adopting a purely defensive approach.”10

They further note that “while transparency might occasionally require an additional effort to be undertaken by the Union’s administration, we believe this to be a worthy trade off in improving the quality of decisions to be taken. It renders decision making and public debate more vivid and accessible.” On a more encouraging note, they observe that “pro-active publication is a pre-condition for accessibility but will also allow reducing the time necessary to react to access requests.”

As we have indicated before, the European Parliament’s own website provides a sound template in an effort to make information more transparent and accessible. As such, while Article 14 TEU on the European Parliament makes no mention of the Parliament’s obligations regarding citizen information or parliamentary groups, the European Parliament has acted pro-actively to inform citizens: it includes a searchable full list of MEPs indicating their Member State and parliamentary group, it provides the results of European elections not only by national party but also by parliamentary group for each Member State and at the EU level, or the number of MEPs of each parliamentary group in each Member State, with comparisons with previous legislatures.

The European Parliament thereby shows a clear commitment to pro-actively providing information relating to stakeholders that are unique to it — the European parliamentary groups — and that would otherwise not be provided by any other institution.

Likewise, and building on the recommendations set out in our initial report, we believe that the APPF should provide, among others, the following information:

- A searchable list of current MEPs, including their Member State, national party, and parliamentary group;

- The results of the 2009, 2014 and 2019 European elections by European party, both at the Member State and EU levels (as well as post-Brexit figures for the EU level), using tables, bar charts and pie charts;

- The outcome of the 2009, 2014 and 2019 European elections by European party in terms of MEPs (as well as post-Brexit figures), using tables, bar charts and pie charts;

- The amount of public funding made available for and received by each European party since 2004, in total amount and percentages, broken down between the lump sum given equally to all qualifying parties and the MEP-based funding, using tables, line charts and pie charts;

- For each year, the number of MEPs used for the calculation of European parties’ MEP-based funding, using tables and pie charts;

- The amount of private funding received by each European party since 2004, broken down between donations, contributions, membership fees and other income, using tables and line charts;

- A timeline of European parties since 2004, indicating the creation and disappearance of parties;

- Membership information for each European party, including its member national parties, using a list (with links to their website) and geographical representation, its number of individual members, and its affiliated political foundation;

- Leadership information for each European party, including, as applicable, its President, Secretary General and Board members;

For most of the points above, the required information is already available in the public domain. While its collection and processing will require work, its periodic update should be fairly easy, as most of the information is either updated on a yearly basis or tied to elections and therefore only amended every five years. The development of templates, including tables, is bound to streamline this process even further.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we argue that the APPF’s reply, with the exception of the point relating to sanctions, does not adequately address the deficiencies identified in our initial report and that its promise to update its website remains far too limited and vague to efficiently remedy the current lack of information and transparency.

We further argue that the treaties endow European citizens with a right to information and obliges each EU institution to make this information transparent. Transparency requires more than the mere republication of information provided by stakeholders and cannot be separated from its full accessibility — including clarity and intelligibility: as highlighted by the European Parliament itself, publication must be made in a way that provides swift, clear and visible answers in response to citizens’ concerns.

For the benefit of European citizens and the formation of their political will, this transparency must apply directly to European parties and foundations. The APPF is the only institution able to provide citizens with a comprehensive view of European parties and foundations, and the best placed to do so. The information published on its website must therefore go beyond the minimum requirements of Article 32(1) and instead meet the needs of a mission of public information — including though the provision of relevant data and figures in context.

We hope the European Ombudsman will recognise in her decision the need for full transparency concerning European parties and foundations, as well as the APPF’s unique role in providing this information. Consequently, we hope the Ombudsman will agree that the APPF must not only properly meet its obligations from Regulation 1141/2014, but also fully take on its public mission of information as the authority on European parties and foundations.

As we have indicated before, we wish to reiterate the constructive nature of this initiative and have already mentioned to the APPF our availability to support their work. Noting that the APPF’s appropriation for the 2021 EU budget is set to increase from €285,000 to €300,000,11 we hope that the European Parliament will also commit to strengthening the staff and financial resources of the APPF,12 as well as the technical and IT support it provides to the Authority, in order to provide it with the full means to fulfill its essential mission for our European democracy.

- “The European Parliament shall make public, under the authority of its Authorising Officer or under that of the Authority, on a website created for that purpose, the following […]” (emphasis added).

- The mention of “Donations received by European political parties and European political foundations within six months prior to elections to the European Parliament” in Article 20(3) only refers to their communication by parties to the Authority and does not limit the publication of donations by the Authority to only those donations made within six months of the European elections.

- Sophie van Bijsterveld, A Crucial Link in Shaping the New Social Contract between the Citizen and the EU, in Transparency in Europe II Public Access to Documents in the EU and its Member States, p.28, 25-26 November 2019

- Emily O’Reilly, How transparent are the EU institutions?, CEPS, 23 May 2018

- Roberta Panizza, Transparency, integrity and accountability in the EU institutions, Briefing for the PETI Committee, Policy Department for Citizens’ Rights and Constitutional Affairs, Directorate-General for Internal Policies, European Parliament, March 2019. Emphasis added.

- Anoeska Buijze, The principle of transparency in EU law, Uitgeverij BOXPress, p.62

- Ibid., p.4

- Ibid. 3, p.29

- Pavel Svoboda, Opinion of the Committee on Legal Affairs for the Committee on Constitutional Affairs on transparency, accountability and integrity in the EU institutions (2015/2041(INI)), 5 February 2016

- Herwig Hofmann and Päivi Leino-Sandberg, An agenda for transparency in the EU, European Law Blog, 23 October 2019

- See draft EU budget 2021: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/budget/data/DB/2021/en/SEC01.pdf#page=76

- See draft budgetary plan 2020 of the APPF: http://www.epgencms.europarl.europa.eu/cmsdata/upload/ae3c2263-fbfe-4402-a9d5-b432a1dfd1c8/Draft_budgetary_plan_2020.pdf

Pingback: EDC responds to Ombudsman decision on Authority for European Parties