The third edition of European Democracy Consulting’s annual Geographical Representation in EU Leadership Observatory (EU-GRLO) reveals a worsening of European citizens’ representation in leadership positions, and calls on Member States and EU institutions — in particular the European Council and Commission — to take strong action to ensure a fairer representation for all European citizens.

In January 2021, European Democracy Consulting published its first annual Geographical Representation in EU Leadership Observatory (EU-GRLO). For the first time, reliable data examined, in a systematic and detailed manner, the level of geographical representation of EU citizens in European institutions.

The 2022 edition confirmed three major conclusions of our Observatory: the overall combined dominance of Western and Southern Europe, together receiving over 80% of all appointments since the EU’s 2004 enlargement, and over 90% of appointments to EU institutions — the most prestigious and publicly visible positions; the unique situation of Northern Europe, with a limited representation in absolute numbers, but far outpacing all other regions when adjusting for population sizes; and the clear and continued under-representation of Central and Eastern European citizens since their accession to the EU, most often in the single digits.

Today, our Geographical Representation in EU Leadership Observatory 2023 provides a useful update of last year’s observations and allows us to measure the progress — or lack thereof — accomplished in 2022 and over the 2020-2022 triennium. Following its analysis of recent appointments and medium-term trends, the EU-GRLO concludes with actionable recommendations aimed at improving geographical representation in our European institutions. Once again, our research rests on a fully public dataset, which was revised and upgraded so as to better serve the scientific community and public authorities.

We wish to warmly thank all the EU institutions, bodies and agencies that have cooperated with this survey by providing information on their leadership in a timely manner. Their support and commitment to transparency is much appreciated. Of course, we welcome corrections for any identified error in our dataset.

Find here our press release and follow us on Twitter at @EDC_eudemocracy.

© 2023 European Democracy Consulting

Third edition of the Geographical Representation in EU Leadership Observatory, published in January 2023.

European Democracy Consulting publications are independent of specific national or political interests. They are based on objective facts and data and reflect our analysis. The Geographical Representation in EU Leadership Observatory and its 2023 edition constitute pro bono work and were not commissioned by any third-party.

The Geographical Representation in EU Leadership Observatory 2023 and its related dataset by European Democracy Consulting are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the publication as well as to remix and adapt it, provided it is only for non-commercial purposes, that you appropriately attribute the publication (European Democracy Consulting, https://eudemocracy.eu/geographical-representation-in-eu-leadership-observatory-2023), and that you distribute it under an identical licence.

For more information on this licence visit the Creative Commons website: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/

European Democracy Consulting

Telephone: +33(0)7.81.03.32.87

Email: contact@eudemocracy.eu

Website: https://eudemocracy.eu/

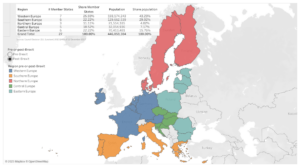

Data and design: European Democracy Consulting

#0B5CBF;">AbstractThe Geographical Representation in EU Leadership Observatory 2023 (EU-GRLO) updates our analysis of geographical representation among the European Union’s leadership positions. The regions surveyed are Western, Southern, Northern, Central, and Eastern Europe, and the positions are the executive leaders of the EU’s institutions, advisory bodies, agencies and other bodies. The 2023 Observatory covers 73 EU entities, 90 positions, and 512 office-holders from 1952 to the end of 2022. Given the EU’s dual emphasis on Member State equality and population-based proportionality, this Observatory questions regions’ equality from three different angles: as equal between one another, pro rata of their number of Member States, and pro rata of their population sizes. Given Member States’ differentiated dates of accession, the Observatory also allows a focus on more recent years (especially after the 2004 EU enlargement, which saw ten countries from Central and Eastern Europe accede to the Union), as well as on Member States’ first years of membership. In particular, this 2023 update reviews appointments made in 2022 and in the 2020-2022 triennium, and assesses recent trends in geographical representation. The Observatory concludes with a series of actionable recommendations to improve geographical representation in the EU’s leadership. KEY WORDS: geographical representation; regional representation; leadership; East-West divide; European Union; European institutions. |

#0B5CBF;">Key figures and survey conclusionsNote: whether based on regional equality, on regions’ number of Member States, or on their population, for each of the five regions to achieve equal representation means reaching a 20% “equality mark” — or one fifth per region.

|

#0B5CBF;">Recommendations

|

Table of Contents

Context

Institutions, bodies and agencies and positions observed

The 2023 EU-GRLO retains our established grouping of EU entities as Institutions of the European Union, Advisory bodies to the European Union, Agencies of the European Union, and Other EU bodies.1

- Institutions of the European Union: the seven entities listed in Article 13.1 of the Treaty on European Union and two legacy institutions — the Commission of the European Atomic Energy Community and the High Authority of the European Coal and Steel Community. For these entities, we focus on the President, who is often a public figure, in particular for the so-called “top jobs”.2 We also cover the positions of Secretary-General for the European Commission, the European Parliament, and the Council of the European Union, of members of the Executive Board for the European Central Bank, and of Vice President, Registrar, and Secretary-General for the Court of Justice and Court of Auditors.

- Advisory bodies to the European Union: three entities created by the European treaties, but lying outside of the main institutional framework (Articles 13.4 TEU and 38 TEU). They have no legislative or decision-making powers, and their main role is to advise EU institutions. One of them, the Political and Security Committee, is headed by the High Representative of the European External Action Service (HR/VP); given its composite structure, the EEAS and its HR/VP are placed in this category. For advisory bodies, we cover the positions of President (and HR/VP, as relevant) and Secretary-General.

- Agencies of the European Union: EU agencies form a diverse group of decentralised bodies established for specific tasks and endowed with their own legal personality. Their fields of work are extremely diverse, ranging from law enforcement, to health, transportation, etc. EURATOM agencies are included, but not Joint Undertakings (public-private partnerships set up under the Horizon 2020 programme). For agencies, we focus on the top executive position, usually called Director or Executive Director.3

- Other EU bodies: finally, the EU has set up a number of other independent bodies for specific purposes, which are best placed together in a category of their own, despite their unique characteristics. These include, for instance, the Authority for European Political Parties and European Political Foundations (APPF), the Office of the European Data Protection Supervisor (EDPS), and the European School of Administration (EUSA). For these bodies, we focus on the single top executive position, with the exceptions of the European Investment Bank, European Investment Fund, and European University Institute. The specific names of these positions vary widely depending on the entity, ranging from the classic Director, to names reflecting the Office in question, such as European Ombudsman, European Data Protection Supervisor, or European Public Prosecutor.

Institutional changes in 2022

Unlike the 2022 edition of the EU-GRLO, the 2023 update does not introduce any changes in terms of entities or positions surveyed. The EU’s most recently created entity — the European Union Agency for the Space Programme, which took over from the European GNSS Agency — was set up in May 2021. Likewise, the executive agencies of the Commission have not changed since their major reshuffling of 2021.4

Finally, Member States are currently discussing the location of the EU’s future Anti-Money Laundering Agency (AMLA). This agency was proposed by the European Commission in July 2021, and both the European Parliament5 and Council6 have now agreed to its setup; it is expected to become operational in 2024.7

Considerations on representation and legitimacy

As stated in previous editions of the EU-GRLO, the first and foremost criteria for the appointment of leadership positions must be and remain individual competence, whether it is called merit, expertise, experience, etc. Of course, ideology may be another important element in the case of political appointments.

However, while differences in levels of representation may be understandable between demographic sub-groups, the clear and continued lack of representation of large segments of the population (in the case of the EU, of national or regional sub-groups) is detrimental to citizens’ feeling of proper representation and, therefore, to their trust in public institutions. This impact may eventually affect voter behaviour and, parting, the “europeanness” of national leaders, which in turn would impact EU governance and cohesion.

Noting the continued rise of Eurosceptic feelings and illiberal policies in Central and Eastern Europe, it is most timely to review the sociology of European leaders, with a particular focus on their national citizenship, so as to address imbalances that may further alienate the citizens of certain of our Member States.

Observatory data and analysis

Overall figures

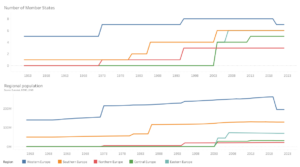

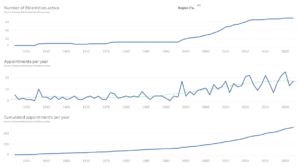

The first edition of the EU-GRLO progressively refined the analysis of long-term data, in order to account for each of the five regions’ number of Member States and own population, as well as for the progressive expansion of the Union membership.

Note: for the 2023 edition of the EU-GRLO, our calculations on Tableau were entirely reviewed in order to simplify our dataset, while fully accounting for the progressive evolution of regions’ number of Member States and population sizes; this explains limited discrepancies in figures with previous editions.8

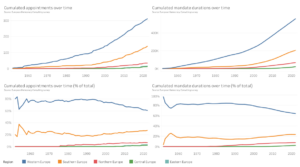

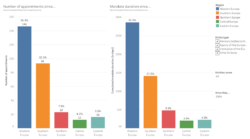

We find that focusing on recent years (whether from the 2004 EU enlargement, or even more recent years) only provides, at best, a limited re-balancing that does not affect general patterns of regional representation. Regions remain far from equal in the representation of their citizens, and only by looking at the most recent years and accounting for regions’ population do Central and Eastern Europe fare slighter better. As such, with 18.9% of all appointments made since May 2019 and pro rata of population sizes, Central Europe almost reaches its fair share — the 20% “equality mark” that each of the five regions should receive for equal representation —, while Eastern Europe reaches a maximum of just 13.8%; these figures, under these specific conditions, seem to be these regions’ highest levels of representation.

By contrast, Western and Southern Europe consistently exceed their fair share of representation in absolute terms and pro rata of their number of Member States. With regards to representation pro rata of their population, they hover around the 20% equality mark in recent years, with Western Europe sometimes slightly below and Southern Europe regularly above.

Finally, despite low overall numbers, Northern Europe almost reaches its fair share pro rata of its number of Member States, and obtains close to twice its fair share of representation when accounting for its limited population.

#0B5CBF;">Key figures

|

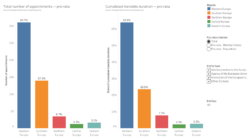

Additionally, our per-Member State overview of appointments within a fixed duration confirms that, with the exception of a few outliers, citizens from Central and Eastern European Member States received fewer appointments than citizens of other Member States following their Member State’s accession to the Union.

This conclusion remains true when factoring in Member States’ populations, and is even more explicit when accounting for the total number of appointments made — whereby the progressive increase in EU entities and, therefore, in the number of leadership positions to be filled makes it relatively easier to appoint citizens from all regions than it was, for instance, in the 1990s.

#0B5CBF;">Key figures

|

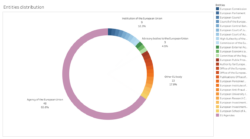

Finally, a more qualitative analysis of appointments by type of entity shows that the appointements received by citizens of Central and Eastern Europe are overwhelmingly for less public or prestigious positions — with agency positions accounting for, respectively, 83% and 69% of appointments for citizens from Central and Eastern Europe. Conversely, EU agencies only account for just over a third of appointments received by citizens from Western and Southern Europe. To this date, no Central European citizen has ever been appointed to any of the positions recorded for EU institutions, nor for our category of “Other EU bodies”.

#0B5CBF;">Key figures

|

Overall, we see that the analysis of appointments to leadership positions is affected by a number of factors: a region’s number of Member States, its population, the amount of time since the accession of its Member States, the number of years taken into account, and the categories of entities considered. However, despite changes in figures, one constant trend remains: the clear and continued under-representation of citizens of Central and Eastern Europe within the EU’s leadership, in particular in the most public and visible leadership positions.

Let us now see whether recent appointments, in particular those of 2022 and of the 2020-2022 triennium, have impacted this representation.

2022 figures and recent trends

Published in January 2021, the original EU-GRLO concluded with specific and actionable recommendations for the improvement of geographical representation in EU leadership positions, ranging from a clear acknowledge of the issue at hand and of its negative consequences, to publishing period data on the matters and committing to remedial action.

While limited time has passed since this initial assessment, this 2023 update to our Observatory aims at taking stock of recent appointments. In particular, we will review mandates starting in the calendar year 2022 and analyse the 2020-2022 triennium.

We recall that a number of recent appointments, decided in late 2022 but only taking effect in January 2023, such as that of incoming Secretary-General of the European Parliament Alessandro Chiocchetti, are not recorded.

Mandate evolution in 2022

For the year 2022, European Democracy Consulting identified seventeen new mandates — four more than in 2021.9

- Three for EU institutions: Roberta Metsola as President of the European Parliament, Thérèse Blanchet as Secretary-General of the Council of the European Union, and Tony Murply as President of the European Court of Auditors;

- One for EU advisory bodies: Vasco Alves Cordeiro as President of the Committee of the Regions;

- Two for Other EU bodies: Nicolas Panayotopoulos as President of the European Investment Fund, and Xavier Matheu as Director of the the European Training Foundation; and

- Twelve for EU agencies, including the EU Agency for Law Enforcement Training, the European Border and Coast Guard Agency (FRONTEX), the European Chemicals Agency (ECA), the European Health and Digital Executive Agency (HaDEA), the European Joint Undertaking for ITER and the Development of Fusion Energy (F4E), the European Research Council Executive Agency (ERCEA), the European School of Administration (ESA), the European Union Agency for the Operational Management of Large-Scale IT Systems in the Area of Freedom, Security and Justice (eu-LISA), and the Translation Centre for the Bodies of the European Union (CdT).

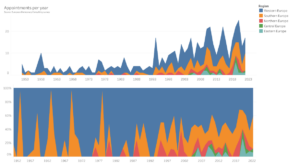

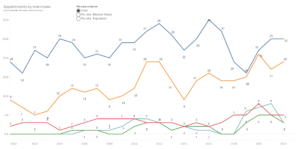

Out of these seventeen new mandates, seven (or 41%) went to Western Europe, eight to Southern Europe (47%), one to Central Europe and to Eastern Europe (6% each), and none to Northern Europe. When calculating pro rata of each region’s number of Member States, the distribution remains more or less unchanged.

When calculating pro rata of each region’s population, Western and Southern Europe remain solidly above the 20% equality mark — at 25% and 43% of all appointments, respectively. Central Europe finally reached its equality mark, with 22%, while Eastern Europe remains squarely below, at 10%.

Beyond new appointments, a complementary information is that of the number of mandates ending in 2022. European Democracy Consulting recorded nineteen mandates ending in 2022 – up from twelve in 2021: nine for Western Europe (47%), five for Southern Europe (26%), four for Northern Europe (21%), one for Eastern Europe (5%), and none for Central Europe.

Overall, the number of EU leadership officer-holders decreased by two for Western Europe (decreasing its over-representation), increased by three for Southern Europe (increasing its over-representation), decreased by four for Northern Europe (decreasing its over-representation), and increased by one for Central Europe (limiting its under-representation).

#0B5CBF;">Key figures

|

Mandate evolution in the 2020-2022 triennium

Of course, while appointments in individual years matter, it is statistically difficult to extract trends from such small samples. This is why the EU-GRLO also analyses appointments in running three-year brackets between 2000 and 2022 (1998-2000, 1999-2001, etc., 2020-2022), in an attempt to smoothen drastic year-on-year variations caused by limited numbers of (or sudden increases in) appointments per year.

Over the 2020-2022 triennium, European Democracy Consulting recorded 55 new mandates, making the data more statistically significant; this is a decrease from 60 appointments in the 2019-2021 triennium, despite 2022 recording a 31% increase in appointments compared to 2021. This is likely due to this triennium’s loss of 2019 which, as an election year, saw a particularly large number of appointments.

Analysis of the data for the 2020-2022 triennium is in keeping with 2022. Overall, citizens from Western Europe still received over twice their fair share of appointments (with 25 appointments, or 46%) and those of Southern Europe remain solidly above the equality mark (with 19 appointments, or 35%). Unlike for the 2019-2021 triennium, Central and Eastern Europe only received three appointments each (or under 6%), compared with respectively 8 and 13% in the previous triennium.

Pro rata of each region’s number of Member States, the distribution is quite similar, with Western and Southern Europe anchored above the equality mark (at 38% and 33%), Northern Europe just below (under 18%), and Central and Eastern Europe trailing behind (with just over 6 and 5%).

As always, the calculation pro rata of each region’s number of citizens is more balanced, but with the same structure. Western and Southern Europe are around the equality mark, at 20 and 23%; Central Europe increases to almost 15%; and Eastern Europe stays under 7%. Northern Europe maintains its usual per capita over-representation, with close to 36% of new mandates in the 2020-2022 triennium.

In the same time frame, European Democracy Consulting recorded 52 mandates ending (down from 55 in the 2019-2021 triennium), mostly for citizens of Western and Southern Europe (23 and 17, respectively). As a result, Northern Europe lost four office-holders over the triennium, while all other regions won (one for Central Europe, two for the other regions).

Overall, we note a confirmation of last year’s prediction. In January 2022, we had noted that the 2019-2021 triennium was encouraging, but that it was also noticeably better than figures for the year 2021 alone, indicating that these positive trends were not stable. Indeed, 2022 has not proven a good year for geographical diversity, and the 2020-2022 triennium falls short of the progress displayed by its predecessor.

#0B5CBF;">Key figures

|

Mandate evolution by entity

Beyond the sheer number of mandates starting and ending in a given year or triennium, it is also interesting to analyse appointments by entity.

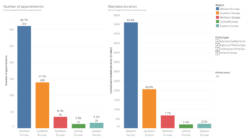

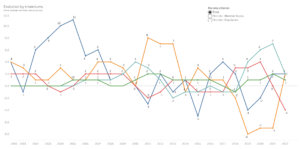

As recalled above, previous editions of the EU-GRLO showed the prevalence of less prestigious, and therefore less visible, appointments for Central and Eastern Europe — with Central Europe receiving over 83% of its appointments from EU agencies and the remaining 17% from advisory bodies. By contrast, Western and Southern Europe receive just under a third of their appointments from EU institutions — arguably the most prestigious and publicly visible positions — and slightly over a third from EU agencies.

Given the limited number of appointments per year or triennium, figures for 2022 or 2020-2022 show sharper contrasts and must be handled with care, but it remains enlightening to look at comparisons between regions.

At this point, it is important to reiterate that we do not consider agency leadership positions less important than other leadership appointments. However, the more prestigious and visible a position, the more European citizens are likely to be aware of the office-holder’s appointment, and the more it contributes to the feeling of representation of the citizens of the same Member State or region as the office-holder.

Our data shows that, in 2022, leadership positions within European institutions formed close to 29% of all appointments for citizens of Western Europe, and 13% for Southern Europe — but 0% for Central and Eastern Europe (Northern Europe, for its part, did not see any of its citizens appointed in 2022). Conversely, leadership positions of EU agencies accounted for 57 and 63% of appointments for Western and Southern Europe, but 100% for both Central and Eastern Europe.

The breakdown for the triennium retains the same imbalances. Between 2020 and 2022, Western and Southern Europe received, respectively, 20 and 16% of their appointments from European institutions, and “only” 52 and 42% from EU agencies. In the same period, Central and Eastern Europe still received 100% of their appointments from EU agencies, meaning that, over the past three years, not a single citizen from Central or Eastern Europe was elected to a non-EU agency leadership position.

Therefore, despite the amount of time that elapsed since the accession to the Union of even its most recent members (the massive 2004 EU enlargement to Central and Eastern Europe was now almost 19 years ago), we note that the breakdown of appointments by entity for the latest triennium is extremely similar to (or worse than) overall values. This indicates that, beyond marginal improvements, very little has actually been accomplished in terms of appointing citizens of Central and Eastern Europe to positions more visible to European citizens — an essential element for the construction of a sense of belonging and integration.

#0B5CBF;">Key figures

|

Who is responsible?

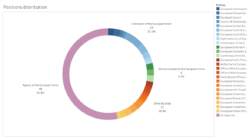

The first three recommendations formulated by the EU-GRLO in 2021 were to acknowledge the lack of proper geographical representation in the EU’s leadership, to acknowledge the likely negative impact of this lack of geographical representation, and to acknowledge the Council and Commission’s central role in appointments and, therefore, in the improvement of geographical representation.

Given this central role, the Council and the Commission are the ones who ought to acknowledge the above, before deciding on corrective and remedial action. But just how central is this role? How can we attest of these two bodies’ predominant role in the appointment of EU leaders?

Appointments by nominating body

In order to answer this question fully, we must look at the nomination processes for the entities observed. The choice of EU leaders is, broadly speaking, made either by nomination or by election. Given the functioning of the European Union, the lines between nomination and election are often blurred: in many instances, an individual is, in name, elected but, in practice, the decision is the result of discussions and compromises, and competing candidates drop out before the vote. Likewise, official announcements often indicate that an individual was nominated or appointed, even when the official mechanism included an election.

Institutions of the European Union

- European Commission. The President of the European Commission is nominated by the European Council as part of the EU’s “top jobs” following European elections. Despite being subject to approval by the European Parliament, the decision-making process of 2019 clearly showed the European Council’s upper hand. The Secretary-General of the European Commission is nominated by the President of the Commission.

- European Council/Council of the European Union. The President of the European Council is nominated by the European Council as part of the EU’s “top jobs”. The Secretary-General of the Council of the European Union — the General Secretariat of the Council assists both the European Council and the Council of the EU — is nominated by the Council.

- European Parliament. The President of the European Parliament is elected by Members of the European Parliament. The Secretary-General of the European Parliament is nominated by the President of the European Parliament.

- European Central Bank. The President of the European Central Bank is nominated by the European Council as part of the EU’s “top jobs”. The Vice-President and other members of the Executive Board of the European Central Bank are also all appointed by the European Council.

- Court of Justice of the European Union/European Court of Justice. The President, Vice-President and Registrar are elected by the members of the Court.

- European Court of Auditors. The President and the Secretary-General of the European Court of Auditors are elected by the members of the Court.

Advisory bodies to the European Union

- European External Action Service. The High Representative/Vice President (HR/VP) is nominated by the European Council as part of the EU’s “top jobs”. The Secretary-General of the European External Action Service is nominated by the HR/VP.

- Committee of the Regions. The President of the Committee of the Regions is elected by the CoR Assembly. The Secretary-General of the Committee of the Regions is nominated by the CoR Bureau.

- European Economic and Social Committee. The President of the European Economic and Social Committee is elected by the EESC Plenary. The Secretary-General of the European Economic and Social Committee is nominated by the EESC Bureau.

Other EU bodies

Given the wide differences in statutes between the entities of this category, the modalities for elections and nominations are very variable. Several entities are directly under the remit of an EU institution; for instance, the European Commission, which appoints the Director of the European Personnel Selection Office, the President and Secretary-General of the European Research Council, the Head of the European School of Administration, and the Director-General of the Publications Office of the European Union. Likewise, the European Parliament elects the European Ombudsman.

On the other end of the spectrum are entities endowed with boards (whether a Governing Board, Board of Directors, High Council, etc.) tasked with the nomination of the entity’s top leadership, such as the Director of the European Institute of Innovation and Technology, the President of the European Investment Bank, the Chief Executive of the European Investment Fund, or the President of the European University Institute. Oftentimes, the Secretary-General of these entities will in turn be nominated by the top leadership, as for the Secretaries-General of the European Investment Bank, European Investment Fund, or European University Institute.

Finally, a number of entities share their accountability to two or more EU institutions. For instance, the European Chief Prosecutor and the European Data Protection Supervisor are appointed jointly by the European Council and the European Parliament. Likewise, the Director-General of the European Anti-Fraud Office and the Director of the Authority for European Political Parties and European Political Foundations are appointed jointly by the European Council, the European Parliament and the European Commission. In these cases, it is not easy to know whether the decision-making process truly gives an equal say to all institutions involved and, if not, where the real decision is made.

Agencies of the European Union

There are too many agencies to cover them all in detail. Broadly speaking, and from the point of view of the appointment of their top leadership, there are three main categories for EU agencies.

The first one is made up of the European Commission’s executive agencies. As the name suggests, these agencies are squarely under the authority of the European Commission which is responsible for the appointment of their (Executive) Directors.

The second group is the most common and sees the Board (or one or more of the Boards) of the agency appoint the Head of the agency. A short review of agencies’ legal bases shows a trend towards the harmonisation of agencies’ internal structure as well as of the nomination process of their top leadership. Most recently created or recently amended Regulations describing agencies now confer upon the European Commission the duty to provide a shortlist of candidates, and on voting members of a Board (often called the “Management Board”) the right to select their preferred candidate.

A last category is made up of special cases or agencies that have not yet been reformed to fit under the above second category — although it remains unclear whether such plans for reform exist. Examples include the Chief Executive of the European Defence Agency, nominated by the European External Action Service, or the President of the Community Plant Variety Office, nominated by the Council of the European Union.

#0B5CBF;">Key figures

|

Appointment by category

The above information provides an overview of which body or group appoints the office-holders recorded by the EU-GRLO. However, in many instances, the ultimate decision-makers may not appear clearly, especially to citizens unfamiliar with European institutions. It is therefore useful, for transparency purposes, to re-arrange the nominating bodies identified according to their own members.

An easy example is that of the European Council and Council of the European Union. When we say that the “top jobs”, among many others, are appointed by the European Council, we are actually saying that the Heads of States or governments of Member States are responsible. Let us then briefly review the various nominating entities.

- European Council and Council of the European Union. The European Council is made up of Heads of States or governments of the Member States. The Council of the European Union is made of the ministers of Member States, gathering in thematic configurations.

- European Commission. Assuming that the appointment of the EU’s top leadership is under the ultimate responsibility of the President of the European Commission, these appointments are made by an EU civil servant politically appointed by the Member States.

- European Parliament. The European Parliament of composed of EU representatives directly elected by citizens.

- Court of Justice of the European Union. The Court of Justice is made up of legal experts appointed by their respective Member State governments.

- European Court of Auditors. The Court of Auditors is made up of legal experts appointed by their respective Member State governments.

- European External Action Service. Assuming that the appointment of the EU’s top leadership is under the ultimate responsibility of the High Representative, these appointments are made by an EU civil servant politically appointed by the Member States.

- European Economic and Social Committee Plenary. Members of the EESC Plenary are EU representatives nominated by their respective Member State governments and appointed by the Council of the European Union, itself composed of government ministers. Members of the EESC Plenary elect the EESC Bureau.

- Committee of the Regions Assembly. Members of the CoR Assembly are EU representatives nominated by their respective Member State governments and appointed by the Council of the European Union, itself composed of government ministers.

- Entity Board. As we have indicated, there is a wide array of configurations for entity boards, making a strict categorisation impossible. However, the large majority of entity boards tasked with leadership appointments (whether EU agencies, the European Institute of Innovation and Technology, the European Investment Bank, the European Investment Fund, or the European University Institute) comprise, among their voting members, representatives of Member States government or of national institutions, which form the majority of the board’s votes. Additionally, boards often include one or more representatives of the European Commission, as well as, for instance, representatives of the European Parliament (ACER, EMA), Council (ACER), workers’ and employers’ organisations (CEDEFOP, EU-OSHA, Eurofound), or UNHCR (EUAA).

In line with the EU’s nation-centric structure, most of the nominating bodies can therefore be traced back to national governments, either through Heads of State or government, ministers, government representatives, national heads of specialised institutions, or EU representatives, civil servants or experts appointed by Member States. In fact, the only nominating body arguably not linking back to national governments is the European Parliament — made up of EU representatives directly elected by European citizens.

Of course, we are not arguing that all those with ties to a national government are considered mouthpieces of their Member State. For instance, experts appointed by Member States, such as judges on the Court of Justice or auditors on the European Court of Auditors, are likely to be less sensitive to national desiderata. The same, however, cannot be said of Member State representatives on agency boards or of more political appointments, such as the “top jobs” or for local elected officials appointed to the Committee of the Regions.

This re-arrangement better displays those responsible for the appointment of the EU’s top leadership and, therefore, where the impetus must come from for the improvement of geographical representation in the EU’s leadership.

#0B5CBF;">Key figures

|

Recommendations

Remedial measures must be considered by a range of actors, but first and foremost — as we have seen above — by Member State governments and their representatives and appointees in EU entities.

Following an in-depth discussion across the EU, the Council and the Commission should adopt a joint commitment declaration with clear action points. Understandably, given the sensitivity and political nature of this issue, it may be easier to agree on broad objectives rather than on concrete figures.

Here are necessary acknowledgements and actionable recommendations for action that should feature in this declaration. Unfortunately, given the Council and Commission’s lack of response and action following previous editions of the Observatory, our recommendations remain largely the same as in previous years.

1. Acknowledge the lack of proper geographical representation in the EU’s leadership

The first step in addressing under-representation is to acknowledge its existence. This Observatory lists ample and verifiable data highlighting the severe lack of representation of Central and Eastern European citizens in EU leadership positions, especially at the highest levels.

The Council and Commission may decide that appointments ought to be made solely based on competence, and that the observed lack of geographical representation is a consequence of this policy. However, with Central and Eastern Europe representing 40% of Member States and 20% of the EU’s population, their almost complete absence from EU leadership positions becomes indefensible. The Council and Commission should use these results and acknowledge the imbalances identified.

2. Acknowledge the likely negative impact of this lack of proper geographical representation

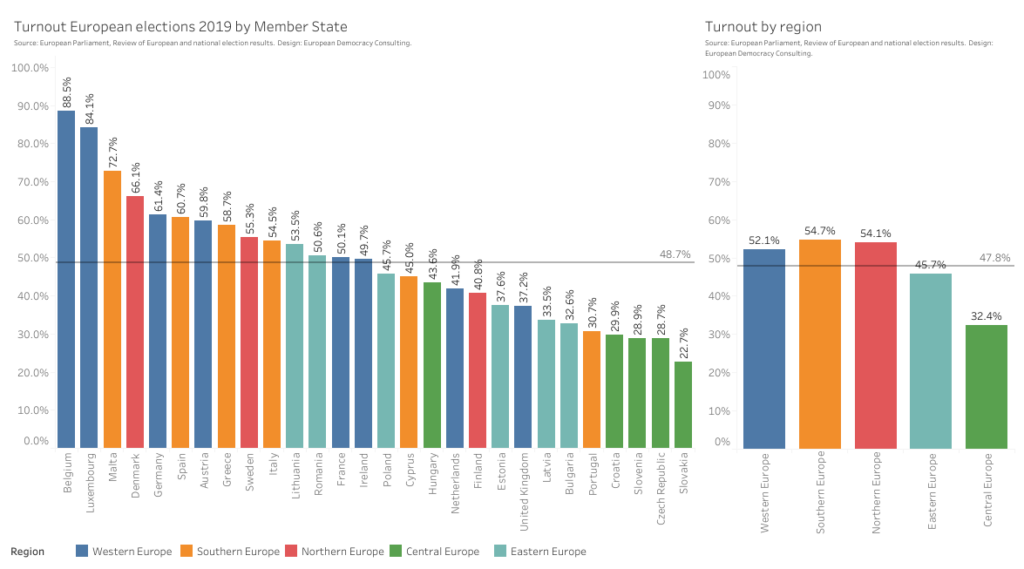

Several countries in Central and Eastern Europe — first and foremost, Hungary and Poland — have given rise to illiberal-minded governments which have repeatedly acted to undermine the rule of law, a treaty-enshrined value of the European Union.10 The limited participation of these regions in European elections should also be a concern: in 2019, nine out of eleven countries from Central and Eastern Europe were under the EU’s average turnout (compared to only five out of 17 for the remaining regions), and four out of five Central European countries were the four least-voting countries in the EU, with rates ranging from 30 down to less than 23%. At the regional level, Central and Eastern Europe also have a noticeably lower turnout than the other three. While there are surely a number of other factors at play, it is clear that the absence of citizens of these countries from leadership positions is sure to further alienate their citizens from the Union.

In this light, it is particularly disappointing that previous editions of the EU-GRLO mostly found an echo in Hungarian and Polish pro-government publications or supporters social media, while pro-European officials remained quiet.

3. Acknowledge the Council and Commission’s central role in appointments and, therefore, in the improvement of geographical representation

Last but not least, Member States, by virtue of the European treaties and of EU entities’ statutes, must acknowledge their direct and primary position in the filling of leadership positions and, therefore, their inescapable role in addressing and remedying the lack of proper geographical representation in the EU’s leadership.

4. Establish dimensions of analysis and baseline measures

In order to start addressing the identified lack of representation, the Council and Commission need to know from where they start. They must first identify the dimensions along which the level of proper representation will be assessed. The Observatory highlights a number of measures that can be used: overall representation since the EU’s founding (objectively the least useful dimension), representation since a specific date, representation proportionally to regions’ number of Member States or population, and representation following a number of years of membership. All these dimensions were considered from the perspective of appointments and mandate durations, and broken down by groups of institutions. They can be re-used for the Council and Commission’s analysis.

However, the survey focuses only on successful elections and appointments, and baseline measures must go beyond publicly available data. In addition, the Council and Commission must look at steps ahead of elections and appointments. In the case of elections, the number of candidates from each region and their rate of success. In the case of appointments, and depending on the precise mechanism, the number of candidates from each region considered for a short list, the number of candidates from each region making it to the short list, and their eventual rate of success.

Going one step further, the Council and Commission must consider the current representation of each region among EU civil servants — disaggregated not only by institution, but also by position level — which forms a large pool for non-political appointments. This should cover both career civil servants and contractual staff members.

5. Establish goals and targets

Once these various dimensions and measures have been established, the Council and Commission must agree on their objectives, including a clear long-term goal and one or more time-bound intermediary goals.

As indicated earlier, European Democracy Consulting does not support or promote the strict equality of representation for Member States or regions, as this would put an unwelcome constraint on hires, which ought to remain guided first and foremost by individual competence. Instead, the Council and Commission should commit to a set of flexible targets. For instance, “by 2030, over a running three-year period, each region’s share of appointments pro rata of its population should range between 15 and 25%” (all regions receiving 20% would mean strict equality).

Similar goals must be divised for dimensions not surveyed by the Observatory and presented in the points above. All of these should be further refined by institution type, and be given intermediary goals over the next decade.

6. Define actions

Once goals have been set, the Council and Commission must delineate the specific actions they will take to achieve them.

Ensuring transparency is a precondition for action. While most EU entities already disclose information on their current executive leadership, information on previous leaders is limited, and often times scarce or entirely missing on the details of the selection process. This should be remedied to as part of good governance measures on transparency. While information on short-listed or competing candidates needs not be publicly available, related statistics should be collected in a relevant yearly publication.

Beyond transparency, affirmative action policies are the most obvious proposal and are already used to address other instances of under-representation. In 1997, the Inter-Parliamentary Union (of which all European national parliaments are members, in addition to the European Parliament as an associate member) indicated in its “Plan of Action” on gender representation that “on a strictly interim basis, affirmative action measures may be taken. Wherever the measure chosen is a quota system, it is proposed that the quota should not target women, but that, in the spirit of equity, it may be established that neither sex may occupy a proportion of seats inferior to a given percentage.”

While affirmative action may be politically divisive, the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union already states that “the principle of equality shall not prevent the maintenance or adoption of measures providing for specific advantages in favour of the under-represented sex” (Article 23).

EU institutions have also repeatedly supported measures of this nature. In 2012, the European Parliament welcomed parity systems and gender quotas introduced in some Member States and urged others to consider legislating to facilitate gender balance in political decision-making.11 In 2015, the Council called upon the Commission, governments, political parties and the European and national parliaments to promote a gender-balanced representation — for example by introducing gender-alternate lists, which the European Parliament has since supported.12 Finally, the Commission’s Gender Equality Strategy 2020-2025 includes equality between women and men in decision-making as a priority objective, setting out soft law measures — including data-collection. In 2012, the Commission proposed a Directive, since agreed to by the European Parliament and the Council, setting a target for EU companies listed on the EU stock exchanges to accelerate the reach of better gender balance; the Directive sets a share of 40% of the underrepresented sex among non-executive directors and 33% among all directors.

Similar temporary measures may be taken to ensure proper geographical representation in the EU’s leadership. For instance, “by 2030, over a running three-year period, each region should not receive a number of appointments one-third below or above its population share, with a maximum spread of 10 points”, as shown in our three-year analysis.

#0B5CBF;">Key figures

|

Of course, numbers alone do not fully do justice to proper representation, as different entities have different levels of prestige and public visibility. As such, increasing the number of Central and Eastern Europeans in leadership positions is important, but it is likely to fall short of true proper representation if appointments only concern EU agencies while all top job positions are attributed to Western and Southern Europeans.

In addition to quotas, which focus exclusively on the outcome of the selection process, other measures must be adopted upstream. This includes the overall promotion of diversity among the EU’s public administration. This representation cannot simply be measured as an aggregate, but be ensured across all hierarchical levels, including the ones leading to consideration for leadership positions.

In its 2009 report on Fostering Diversity in the Public Service, the OECD describes diversity “not only as the mixture of backgrounds and competences but also as valuing and using people’s competences, experience, and perspectives to improve government efficiency and effectiveness, and to meet public servants professional expectations.” It highlights a “growing consensus […] that pursuing diversity may also help to preserve core public service values such as fairness, transparency, impartiality and representativeness.” The report notes “a growing tendency to see diversity as an asset rather than as a problem” and encourages governments to include diversity principles “part of any public management reform, as diversity initiatives cannot succeed as an isolated strategy.”

In particular, measures should be considered to “make the recruitment process fairer, more transparent and more flexible to attract talented people with a mix of backgrounds, experience and perspectives. Improvements to the recruitment process refer to the instruments or mechanisms that aim to: i) diversify the communication channels to reach a wider audience; ii) motivate people to apply for vacancies in the public service; iii) relax the selection process and criteria to make them more inclusive but still focused on analysing skills, qualities and competencies required for the job; and iv) facilitate the integration and retention of new recruits to the workplace.”

In a 2019 survey on Managing a diverse public administration or effectively responding to the needs of a more diverse workforce, the OECD further encourages governments to go “beyond technical efficiency to the creation of public value where the civil service aims to deliver better services to all and strengthen the legitimacy of, and confidence in, public sector institutions in the eyes of the public. It suggests the need to design more diverse and inclusive policies and services, supported by more diverse and inclusive public sector institutions. A representative public sector workforce also sends a strong message of inclusion, that public sector institutions are serious about taking all of their citizens’ concerns to heart and designing policies and programs that meet their needs.”

Beyond the Council and Commission, these measures highlight the special role to be played by the European Personnel Selection Office (EPSO), as the office responsible for selecting staff for all institutions, bodies and agencies of the European Union, and the European School of Administration (EUSA), which organises training programmes for staff of EU institutions, bodies and agencies.

7. Track progress publicly

Finally, once actions have been decided, progress along the dimensions identified earlier must be periodically assessed and made public, at least on a yearly basis. If need be, the dimensions themselves may be reviewed and improved in order to better track the impact of the actions taken, and actions should be amended as necessary to ensure long-term objectives are met.

Public scrutiny and clear lines of responsibility, in particular of the Council and Commission, must be guaranteed to ensure that the relevant actors are held accountable. We aim for this Geographical Representation in EU Leadership Observatory to be a significant and useful first step in this direction.

8. act and do not leave the results of this analysis to Eurosceptic movements

As indicated above, previous editions of the EU-GRLO mostly found an echo in Hungarian and Polish pro-government publications or supporters social media. Following the publication of the initial EU-GRLO, two questions were addressed by Members of the European Parliament to the European Commission, asking what the Commission planned on doing to address the geographical imbalances identified by our Observatory; both questions stemmed from members the hard-right European Conservatives and Reformists Group, from the Polish Law and Justice (PiS) party.13 All the while, and despite some media coverage, pro-European officials remained quiet on the topic.

While we understand how social media provides an easy and, very often, disproportional echo chamber for nationalist groups, and while we do not claim that our research makes major headlines, it is not encouraging to see such a one-sided re-use of our data.

Contacted directly and provided with the results of our study, major European institutions were either silent or issued generic responses restating their commitment to diversity. Given the eagerness of nationalist movements to capitalise on this data to attack our common institutions, we can only encourage European institutions and leaders to more actively seize themselves of this topic and actively seek to address the disparities identified for the benefit of all European citizens.

About European Democracy Consulting

European Democracy Consulting is a consulting firm specialising on the provision of legal and political expertise on institutional and constitutional matters. Our goal is the strengthening of European democracy through reform and the application of best-practice measures.

OUR HISTORY

European Democracy Consulting was created in 2019, out of the desire to improve our European democracy. The 2019 European elections have shown a renewed interest for our Union, but also the limits of citizens’ engagement. Following these elections, European Democracy Consulting was set up to help decision-makers, public institutions, and NGOs in their promotion of a more democratic, transparent and efficient European Union.

OUR VISION

Democracy does not always come easy; there may be vested interests opposing its development. As a result, sixty years after its creation, the European Union still falls far short of the democratic standards of developed countries.

We wish to bring our solid expertise to support a value-based discussion and propose concrete political and legal solutions, based on best-practices, that will strengthen our common democracy for the general interest of all Europeans.

- https://european-union.europa.eu/institutions-law-budget/institutions-and-bodies/types-institutions-and-bodies_en

- The European Central Bank is a particular case, in that its composition is the Eurozone and not the full European Union — leaving aside Bulgaria, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Hungary, Poland, Romania, and Sweden. Using our classification, Central and Eastern European countries belonging to the Eurozone are: Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Slovakia, and Slovenia.

- The Fusion for Energy Joint Undertaking (F4E) was included in the EU-GRLO as one of the only two bodies, alongside the EURATOM Supply Agency, set up under the EURATOM treaty. Conversely, the Computer Emergency Response Team (CERT-EU) was not included, despite its inter-institutional nature, as it is an administrative unit of the European Commission’s Directorate-General for Informatics.

- In the same way as we had handled previous institutional changes (such as with the European Parliament, initially set up as the Common Assembly of the European Coal and Steel Community in 1952), and in an effort to be true to the organisational nature of EU entities, we assigned all previous office-holders to the new name when the new agency is a clear successor to a previous one, and created a new entry where the new agency is markedly different from its predecessor(s). For instance, all directors of the GSA and of the INEA are now recorded as having been directors, respectively, of the EUSPA and of the CINEA, even though these agencies bore a different name under their tenure. However, given the heavy restructuring involved, HaDEA is considered a separate entity from the now-defunct CHAFEA.

- https://www.europarl.europa.eu/thinktank/en/document/EPRS_BRI(2022)733645

- https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2022/06/29/new-eu-authority-for-anti-money-laundering-council-agrees-its-partial-position/

- https://www.politico.eu/newsletter/brussels-playbook/designated-survivor-le-maire-habeck-in-dc-qatargate-latest/

- A caveat is that Eurostat’s database only ranges from 1960 to the end of 2021. Populations sizes between 1952 and 1960 were therefore assumed constant; likewise, populations figures for 2022 are the same as that of 2021. The impact on the data is negligeable.

- As for all other data, the point of reference is the office-holder’s first day in office, and not the day the appointment was decided. We also include interim office-holders.

- Treaty on European Union, Article 2: “The Union is founded on the values of respect for human dignity, freedom, democracy, equality, the rule of law and respect for human rights, including the rights of persons belonging to minorities. These values are common to the Member States in a society in which pluralism, non-discrimination, tolerance, justice, solidarity and equality between women and men prevail.”

- European Parliamentary Research Service, Women in politics in the EU State of play, 2019, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2019/635548/EPRS_BRI(2019)635548_EN.pdf

- European Parliament, Legislative resolution of 3 May 2022 on the proposal for a Council Regulation on the election of the members of the European Parliament by direct universal suffrage, 2022, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/TA-9-2022-0129_EN.html

- https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/E-9-2021-000467_EN.html and https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/E-9-2021-000829_EN.html

Pingback: GRELO2024 – EDC