In 2021, European Democracy Consulting published the first detailed analysis of European political parties’ donations and contributions, covering the years 2018 and 2019, to remedy the lack of contextual and visual information provided by the Authority for European Political Parties and European Political Foundations (APPF) on its website. Today, we are updating this data with figures for 2020, providing more detailed information, and adding maps for a better overview of European parties’ private funding.

#0B5CBF;">Summary and findingsThis report updates our 2021 analysis of European parties’ donations and contributions, which now covers the years 2018 to 2020. It also provides a finer analysis of our data, a special focus on donations above €3,000, and maps and flow charts for a better overview of the origin and destination of European parties’ private funding. Overall, the continued difficulty to access financial information on European political parties, their extreme reliance on European public funding, and the almost non-existent role of small donations underline many shortcomings of Regulation 1141/2014, eight years after its adoption and despite revisions in 2018 and 2019. As the European Parliament and Council begin discussing the upcoming reform of this Regulation, we call on both institutions to seize this opportunity and to make the funding of European parties and its transparency a cornerstone of this revision for the direct benefit of European citizens.

|

#0B5CBF;">Key RecommendationsFollowing our review, we can make the following recommendations in order to strengthen European parties’ private funding, in particular small donations from citizens, as well as the transparency of this funding. Strengthening private funding

|

Reporting donations and contributions

European political parties, like all other political parties, need money for their operations. Since 2004, they receive public funding from the European Union, in addition to their private fundraising. The current framework regulating European parties’ funding — including the structure of public funding and provisions on private funding — is detailed in Regulation 1141/2014.

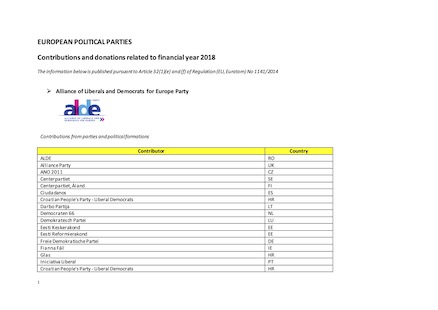

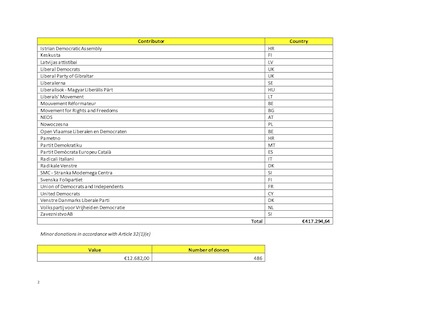

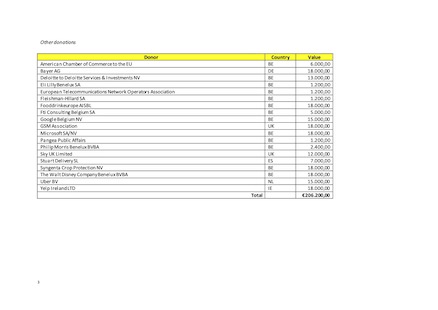

The adoption of Regulation 1141/2014 also set up the APPF, which is mandated to publish the donations and contributions received by European political parties. In a nutshell, “contributions” are defined as payments made by party members (individual member or national member parties), while “donations” are payments made by non-members, including companies and individuals.

However, contributions from individual members of European political parties (including their membership fees) seem to fall through a loophole. Article 32(1)(f) requires the publication of contributions referred to in Article 20(7) (“Contributions to a European political party from its members”, so presumably from both member parties and individual members), but “reported in accordance with Article 20(2)”. Article 20(2), for its part, requires European parties to “transmit a list of all donors with their corresponding donations” and says that this requirement “shall also apply to contributions made by member parties of European political parties” — this time with no mention of contributions from individual members. As a result, the APPF must publish all the contributions transmitted to it by European parties, which they can receive them from both members parties and individual members, but European parties only need to transmit the ones from member parties, despite also transmitting all donations down to the smallest ones. It is unclear whether this situation is intentional; it also seems to go against established practice, since European parties fill in a template which explicitly has a field to transmit to the APPF its amount of contributions received from individual members.

At present, it is unclear whether the APPF publishes only contributions from member parties, or whether there are simply no contributions from individual members. For contributions made in the year 2020, the APPF reported a separate amount for individual contributions for the ECR — this was the first time for any European party for any year. If confirmed, this would indicate that no European party has ever received funding from one of its individual members, not even a membership fee. The APPF has not yet responded to our queries.

While more clarity on the matter would be welcome, the number of individual members of European parties is so low that contributions from individual members are not expected to make a significant difference. For the time being, we will therefore focus on contributions from member parties.

With regards to the information to be reported by the APPF, Article 32(1) requires the publication of:

(e) the names of donors and their corresponding donations reported by European political parties and European political foundations […] with the exception of donations from natural persons the value of which does not exceed EUR 1 500 per year and per donor, which shall be reported as ‘minor donations’. Donations from natural persons the annual value of which exceeds EUR 1500 and is below or equal to EUR 3000 shall not be published without the corresponding donor’s prior written consent to their publication. If no such prior consent has been given, such donations shall be reported as ‘minor donations’. The total amount of minor donations and the number of donors per calendar year shall also be published; (emphasis added)

(f) the contributions […] reported by European political parties and European political foundations […], including the identity of the member parties or organisations which made those contributions;

As a result of these provisions:

- annual donations from legal persons and donations from natural persons above €3,000 are always published with the name of the donor and the corresponding amount;

- donations from natural persons below €1,500 are grouped as minor donations;

- donations from natural persons between €1,500 and €3,000 are published with the name of the donor and their amount if the donor agrees, and as minor donations otherwise; and

- the sum total of contributions is published with the list of contributors, but without the disaggregated amounts.

Visualising donations and contributions

The shortcomings of the APPF in the implementation of its transparency obligations were already the subject of a complaint to the European Ombudsman by European Democracy Consulting.

In particular, European Democracy Consulting noted that financial information was not provided in open data format but in PDF files, that no contextual or visual information was provided for the proper understanding of the published data, and that it took the APPF a disproportionate amount of time to publish information on donations and contributions.1 All three points drastically reduce the effective transparency of European parties’ private funding.

In her January 2021 decision, the European Ombudsman asked the APPF to provide information, in particular financial information, in open data format. Unfortunately, once again, the APPF chose to publish financial data on donations and contributions, for the year 2020, in PDF format. Once again, it decided against providing any visibility or comprehensibility for this financial information, by way of contextual or visual information. And, once again, despite this information being made available by European parties by 30 June 2021 at the latest, it was only fully published by the APPF in late February 2022.

As a result, European Democracy Consulting decided to remedy these shortcomings and provide European citizens with relevant visualisations by updating last year’s analysis of European parties’ donations and contributions. For reference purposes, we would like to indicate that the entire time dedicated to this work — including data collection, data analysis, visualisation design, and website editing — was merely a few days’ work.

Last year’s analysis included the breakdown of parties’ private income between contributions from member parties, identified donations and minor donations, the evolution of these amounts between 2018 and 2019, and a comparison between European parties’ private and public funding. In addition, this year’s review adds specific visualisations for donations above €3,000 — for which the European Commission proposes additional due diligence measures — as well as maps and flow charts for a clear overview of the origin of identified donations and member party contributions.

The related dataset can be found here.2

Visualising donations and contributions

Amounts and shares

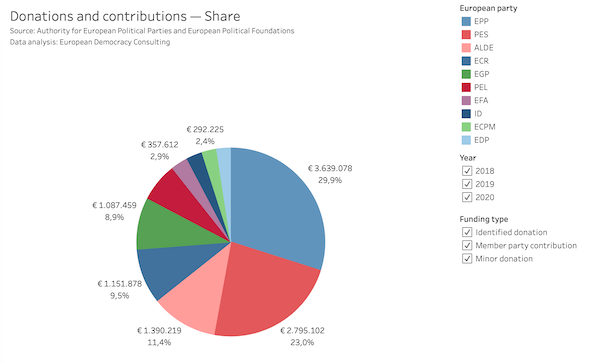

(visualisation here)

The first visualisation presents the simplest of overviews and shows the sum totals of donations and contributions received by the current ten registered European political parties between 2018 and 2020, with the possibility to narrow down the time span. As per the provisions of Regulation 1141/2014 and the data provided by the APPF, each party’s income is split between member party contributions, identified donations (donations for which the identity of the donor is known), and minor donations (which are reported together as an anonymous single amount).

Immediately, we note great disparities between the donations and contributions received by the various European parties, with the EPP and PES largely leading the raising of private funds. The picture is less clear for the remaining parties, with four parties above and below the one-million-euro mark (in increasing order, the PEL, EGP, ECR and ALDE) and four others around €300,000 (the EDP, ECPM, ID and EFA).

Since the EPP and PES are also clearly the largest parties, these discrepancies beg the question of whether larger European parties fare better in the raising of private funds than smaller European parties. This question can be answered by looking at amounts of private funds raised pro rata of European parties’ number of MEPs or of their reimbursable expenditure (the category of expenses used to calculate how much European parties can receive).3 This is a major argument recently used by the European Commission to justify its proposal to lower European parties’ co-financing rate (the amount of private funding requested as a share of European parties’ budget) from 10% in the current Regulation down to a proposed 5% (and even 0% in election years).

Under this angle, the data looks very different and there are no signs that smaller European parties face more difficulties in private fundraising compared to larger ones. When looking at private funds pro rata of European parties’ number of MEPs, the ECPM, the smallest party in terms of MEPs, is a clear outlier, far outpacing all others in the amount of donations and contributions raised per MEP (with close to €77,000 raised per MEP). Then come the EFA, EDP and PEL, raising between €45,000 and €28,000 per MEP). The majority of European parties, including all the largest parties, oscillates around €20,000 per MEP, noticeably below smaller parties. With €7,000 per MEP, ID finds itself alone, far behind all other European parties.

When looking at private funds pro rata of European parties’ reimbursable expenditure,4 differences are less pronounced, but the PEL and ECPM stand ahead, with their private funding making up 11-12% of their reimbursable expenditure. The bulk of European parties oscillates around 8-9%, while ID lags behind with around 3.2%. Neither pro rata views therefore show larger parties fairing better than smaller ones in raising private funds.

#0B5CBF;">Key figures

|

From our first visualisation, we also note that member party contributions form the vast majority of the private funding raised by European parties. A second visualisation looks at this point in more detail and shows the respective percentages of each type of funding. This view confirms the importance of member party contributions, which represent almost 100% of private income for seven of the ten European political parties (actually 100% for four European parties, and above 95% for another three). The remaining three European parties form an heterogeneous group, with member party contributions reaching close to 80% for ALDE, over 50% for the ECR, and under 40% for the ECPM.

As a result of the weight of member party contributions, donations only play a limited role in European parties’ financing. They are nonexistent for six out of ten European parties, and only form a substantial amount for three: 23% for ALDE, 47% for the ECR, and 63% for the ECPM. But even in these last cases, the amounts in question are low: the ECPM’s 63% actually only amount to just over €194.000 over three years. In all cases, minor donations remain marginal, only reaching just over 10% for the ECPM.

#0B5CBF;">Key figures

|

Evolution over time

In the previous visualisations, we looked at sum totals for the period 2018-2020 (or specific years) to compare the amounts of donations and contributions raised by the various European political parties. Let us now analyse this information with a time perspective, which provides two main conclusions.

(visualisation here)

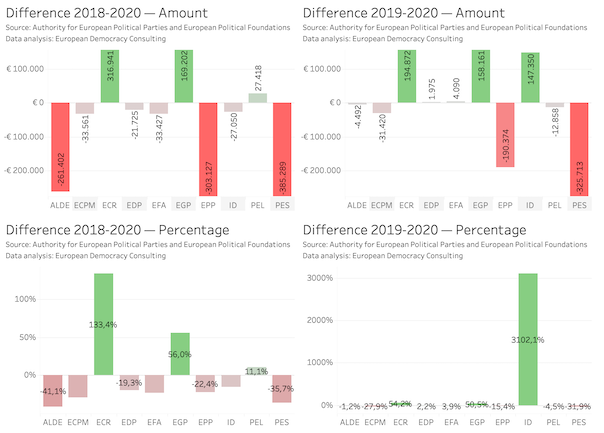

The first observation is that there are no trends in the evolution of donations and contributions raised by European parties. Between 2018 and 2020, we see the EPP and PES raising less money every year, ALDE stabilising after an initial loss, the ECR and EGP raising more money every year, the ECPM, EDP, EFA and PEL rather stable, and ID recovering after a quasi-absence of private funding in 2019.

Additionally, and while the number of years observed remains thus far limited, it seems like “classic” external factors, such as the organisation of elections, do not directly impact the private funding of European parties (whereby we could have expected funding to increase between 2018 and 2019, ahead of the election, and to decrease afterwards). This is confirmed by an analysis of year-on-year differences.

We noted above that, given the organisation of the 2019 elections and the occurrence of Brexit, the years in question show notable year-on-year changes in European parties’ number of MEPs. However, even calculating European parties’ private funds pro rata of their number of MEPs for each year, there remain major variations — meaning the evolution of private funds raised is not merely linked to a party’s changing number of MEPs. Of course, since European elections take place in May, a party may be able to receive substantial donations in the first half of the year and yet see its number of MEPs crumble following the elections: this lower number of MEPs for the year (calculated at the end of the year) would then lead to a high amount per MEP for the year in question. This may explain the strong divergences experienced by the ECPM, which lost half of its MEPs following the 2019 elections (down from 6 to 3).

Likewise, the evolution of European parties’ reimbursable expenditure does not seem to account for these variations. When analysing the evolution of private funding as a share of reimbursable expenditure for 2019 and 2020, amounts are not stable over time and no trends can be identified.

The second observation seems to be a rather stable share of donations, as a fraction of overall private funding raised, for each European party. With the exception of the year 2018 for ALDE, European parties’ shares of minor donations and identified donations appear rather stable over time. For instance, the ECPM and ECR — and, to a lesser degree, ALDE — maintain high shares of donations every year. By contrast, European parties almost not gathering donations (such as the EPP, PEL, PES, etc.) are independent from them every year and, for instance, do not experience a surge in donations ahead of elections. This would seem to indicate that European parties have rather stable fundraising practices — with some regularly relying on donations, and other continuously operating without them (whether or not this is their intention).

#0B5CBF;">Key figures

|

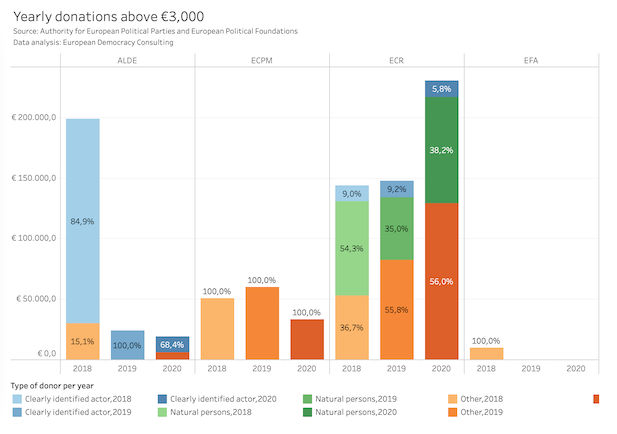

Yearly donations above €3,000

In November 2021, following the European Parliament’s adoption of an implementation report on Regulation 1141/2014, the European Commission published its own legislative proposals to reform the framework on European political parties. As part of these proposals, an amended Article 23 would require European parties to carry out due diligence measures in order to properly identify their donors for donations above €3,000 and to transmit this information to the APPF upon its request.

While generally welcoming due diligence measures as a way to improve financial transparency in the funding of political parties, European Democracy Consulting decided to take a closer look at the effective impact of these proposed measures.

Before any analysis, we note that the European Commission’s proposal currently applies to single donations the value of which is €3,000 and above. However, the figures reported by the APPF are yearly aggregates, which means that values reported above €3,000 may actually comprise two or more donations under €3,000 — or could easily be donated as such in order to avoid scrutiny. This loophole is easily remedied to, but the Commission’s proposal would then need to be amended accordingly.

Overall, the main observation is the limited reach of these due diligence measures. Between 2018 and 2020, yearly donations above €3,000 accounted for 7% of all donations and contributions, for a total sum of €300,000 per year for all European parties combined. Such donations were made to only four European parties: ALDE (14.8% of all donations and contributions), the ECPM (31.8%), the ECR (31.2%), and the EFA (2.7%). For these parties, they accounted for, respectively, €242,000, €144,000, €522,000, and €10,000 over three years.

In terms of numbers of donors with yearly donations above €3,000 (which, once again, can easily be higher than the number of actual donations above €3,000), these due diligence measures would concern very few donors: 47% of the ECR’s donors (46 donors, among which only 41 unique donors), but only 6.5% for the ECPM (18 donors, for 13 unique donors), 1.7% for ALDE (22 donors, for 8 unique donors), and 0.8% for the EFA (1 donor).

#0B5CBF;">Key figures

|

But the sheer amounts of these yearly donations or numbers of donors are not all there is to this. The goal of due diligence measures is to identify the ultimate donor, in order to provide full transparency over who funds political groups. But it may be that the ultimate donor is already known.7 European Democracy Consulting therefore split donors with yearly donations of €3,000 or above into three groups.

(visualisation here)

The first group comprises individual donors. For donations above €3,000, individual donors are required to provide their identity. Due diligence measures are unlikely to provide any significant information about them. The second group is made up of what we call “clearly identified actors”; these are legal persons which are well-established and easily recognisable. Falling into this category are companies (such as Microsoft, Uber or AT&T), non-EU member parties (including, but not limited to, former member parties from the United Kingdom), or well-known lobbies or foundations (such as the Friedrich Ebert Stiftung, Fooddrinkeurope, or the European Telecommunications Network Operators Association). These actors are clearly identifiable and already publicly provide ample information about themselves, making due diligence measures of limited added value. Finally, the third category gathers all other legal entities, for which limited information may easily be available — this includes many smaller and little-known companies, foundations and interest groups. While this categorisation may seem arbitrary, it is likely to match the risk-based decision-making process of the APPF before requesting due diligence information from European parties, as it is unlikely to request such information for clearly identified actors and instead focus on lesser-known entities.

Out of these three categories, due diligence measures are therefore likely to be truly beneficial only for this last category, further reducing these measures’ effective benefit. Out of all yearly donations above €3,000 indicated above (for the four European parties that have received them), the “other” category makes up 55% of the number of yearly donations, and just under 50% in total value. This means that, over the course of three years, these proposed due diligence measures may provide added transparency, at a maximum (that is, if these are indeed single contributions above €3,000 and if the APPF actually requests that information from European parties), for €454,000, and 42 unique donors — out of a total 2,134 total donors.

#0B5CBF;">Key figures

|

Private v. Public funding

The main purpose of this review is to shed light on European political parties’ sources of private funding, including the amounts and shares of donations and contributions, and their breakdown into sub-categories. It is also enlightening, however, to take a step back and compare European parties’ private funding to the public funding they receive, under Regulation 1141/2014, from the European Union.8

As noted before, European public funding represents the vast majority of European political parties’ funding, making them both extremely reliant on public funding and very independent from private donations and contributions, beyond their need to reach the 10% co-financing rate established by Regulation 1141/2014.

At present, the European Parliament’s Political Structures Financing Unit only provides very partial amounts of funding provided to European parties for the year 2020, meaning our analysis can only be relevant for the years 2018 and 2019. As last year, we note that European political parties’ share of private funding is consistent across the board and barely goes beyond 10%. With around 14% each, the EDP and PEL stand out marginally.

#0B5CBF;">Key figures

|

Mapping donations and contributions

In addition to identity and value, which we have used to compute total amounts, shares, evolution and categories of donors, there is one additional piece of information provided by the APPF in its reporting: the country of origin of donations and contributions. This year, we are therefore introducing a mapping of this geographical information to better understand the financial flows received by European parties.

The main limitation here is the lack of data. On the one hand, the APPF provides country information for donations from legal persons and for donations from individuals above €3,000 (and between €1,500 and €3,000, provided they have given their agreement). However, we know that these donations are limited in numbers and value. On the other hand, the APPF provides country information for contributions from member parties, but without indicating the matching value of the contribution (only the sum total of contributions per European party), meaning we can know whether member party X from country Y gave a financial contribution, but not whether that contribution is €1 or €1 million. As a result, we have detailed information on few donations, and only partial information on the much larger member contributions. Finally, no geographical information is provided for minor donations.

Despite this incomplete information, we are able to provide the following visualisations as a first step in the study of the origin of European political parties’ private funding.

#0B5CBF;">Key figures

|

Recommendations

The analysis of European political parties’ private funding highlights a number of shortcomings in the current legal framework of Regulation 1141/2014, both with regards to the scale of this funding and to the transparency of financial data. In order to strengthen European parties’ private funding, in particular small donations from citizens, as well as the transparency of this funding, European Democracy Consulting makes the following recommendations.

Strengthening private funding

- Increase European parties’ co-financing rate. European parties’ co-financing rate (the share of their budget which must come from private funding) has periodically decreased from 25% to 10%; the Commission now proposes to bring it down to 5%, and to 0% in elections years. Despite European parties’ difficulties in raising private funds, this funding is essential in pushing European parties to reach out to citizens and receive their funding. We have seen that, contrary to the Commission’s argument, smaller European parties actually raise more private funding pro rata of their MEP than larger ones. By continuing to decrease this rate, we are therefore not supporting smaller parties, but instead entrenching the disconnect between European parties and citizens. Instead, this rate should return to higher levels, as an incentive for European parties to talk to citizens.

- Reward the raising of donations. Currently, the maximum amount of public funding that European parties can receive is, in its vast majority, based on European parties’ number of member MEPs. This means that, beyond retaining their MEPs, European parties have no direct incentive to raise more donations. By contrast, part of the EU’s public funding should be attributed to European parties using a matching fund, whereby every euro raised from private donations (which excludes member party contributions) would be matched with a fixed amount of public funding — for instance, €0.50. Brackets could be used to make this system regressive — for instance, €0.50 per euro for the first €500,000 raised, and €0.30 after that. Since most European parties do not receive any donations to speak of, an even more highly regressive system, strongly rewarding the first tranches, can help kick-start this private fundraising process. Finally, a ceiling can be set to avoid unexpectedly high costs — for instance, only the first €1 million of private funding would be matched with public funding.

- Limit member party contributions. As we have seen, the vast majority of private funding is actually made up of member party contributions, and is therefore not the result of direct fundraising from the general population by European parties. In order to prevent the capture of European parties by national parties, Regulation 1141/2014 already states that these contributions should not exceed 40% of a European party’s budget. Given European parties’ extreme dependence on public funding, no European party has ever come close to that threshold. However, in order to incentivise European parties to directly raise funds from citizens, a provision should request that member parties’ contribution should not exceed a given share of the total amount of private funds raised — this share could start at 90% (mostly affecting European parties which currently do not receive any donations) and progressively decrease to 50%. This would force European parties to obtain a larger part of their private funding from donations or contributions by individual members.

Improving transparency

- Provide separate deadlines for financial reporting by European parties. Currently, Regulation 1141/2014 requires European parties to provide “the list of donors and contributors and their corresponding donations or contributions” alongside their annual financial statements and external audit reports at the latest six months following the end of the financial year (30 June). However, preparing financial statements and having an audit carried out takes much longer than the mere compilation of donors and contributors. There is therefore no objective reason to provide a single deadline and, as a result, to wait so long for the information on donations and contributions to be made available to the APPF and, later, to the general public. Regulation 1141/2014 should therefore include a separate and shorter deadline for the transmission of financial data on donations and contributions by European parties to the APPF. This would allow the APPF to stagger its work and start its review of donations and contributions earlier on. For instance, European parties could be given one month to share the information with the APPF and, if necessary, an additional two weeks for rectifications.

- Set up deadlines for the publication of donations and contributions and other financial information by the APPF and the European Parliament. While European parties are requested to share their financial information under a fixed deadline, Regulation 1141/2014 does not impose any time limits on the APPF for the publication of financial information. As a result, the APPF has regularly taken seven to eight months to check donations and contributions — for instance, information for the year 2020 was not made fully available until end of February 2022. This is all the more disconcerting given the limited number of donations and contributions made to European parties. Mindful of the important checks carried out by the APPF, Regulation 1141/2014 should contain a time frame for the release of this information by the APPF — for instance, a maximum of three months. This provision should go hand-in-hand with the previous recommendation, whereby the APPF would be able to start verifying donations and contributions before receiving European parties full financial statements and audit reports. Likewise, the European Parliament has no deadline for the publication of the information it is responsible for under Regulation 1141/2014. As a result, European parties’ financial statements (provided within six months of the end of the financial year) are published far too late for proper transparency; as of March 2022, the most recent financial statements published dated back to 2019. Finally, European parties’ applications for European public funding, which contain useful financial information and are currently not published at all, should be made public as soon as they are submitted.

- Publish financial information in open data format. As we have noted, the APPF continues to publish financial information in PDF format only. This is despite a call by the European Ombudsman, over a year ago, for the publication of information, in particular financial information, in open data format. The APPF has previously indicated support for this measure, but has yet to make any progress. This requirement should also apply to financial information already published by the APPF.

- Publish the value of financial contributions made by member parties. European parties are already required to provide the APPF with a list of the contributions they have received, along with the name of the contributors. However, the APPF only publishes the sum total of these contributions, along with the names of the member parties contributing. The value of single contributions made by member parties should be detailed.

- Review the notions of contributions and donations. Contributions are, by and large, financial contributions made by members, be they member parties or individual members; donations are, by and large, financial contributions made by non-members. However, contributions made by individual members fall into a loophole and are not mentioned in the information to be reported under Article 23 (although they seem to appear in European parties’ financial statements). In order to avoid such loopholes, contributions should be redefined as membership-related mandatory financial contributions, while donations should be any voluntary financial contribution — regardless of whether they were made by members (in addition to their mandatory membership fee) or non-members.

- Ensure the publication of single donations. Regulation 1141/2014 requests the APPF to publish “the names of donors and their corresponding donations […] with the exception of donations from natural persons the value of which does not exceed EUR 1500 per year and per donor, which shall be reported as ‘minor donations'” (and donations with a yearly value between €1,500 and €3,000 require the consent of the donor for publication). However, while the threshold for reporting is the amount of donations per year, this language does not make clear whether reported amounts should be aggregated per year or not. This provision should therefore be amended to clearly state that the value of single contributions (when their yearly total meets a given threshold) should be published.

- Lower the ceiling of anonymous donations. As we have seen, donations under €1,500 per year are not reported separately, but instead grouped as “minor donations”, while yearly donations between €1,500 and €3,000 require the consent of the donor for the publication of their name. Since there are a number of minor donations reported (under €1,500) as well as donations over €3,000 made by individuals, it seems unlikely that no donations between €1,500 and €3,000 would have ever been made. And yet, no such donations have even been reported by the APPF. There is therefore a strong suspicion that no individual has ever voluntarily agreed to disclose their identity when this choice is given, which would render the idea of a low €1,500 threshold moot. In order to simplify the donation process and increase transparency, we therefore propose to remove the question of consent and to lower the ceiling for anonymous donations to €500: all donations above would made public, and all donations below would be anonymous and grouped as “minor donations” (unless a single donor makes several such donations for a total of over €500).

- Clarify that due diligence thresholds apply to yearly donations. As detailed above, the European Commission is proposing that European parties carry out due diligence measures for donations above €3,000. This proposal should be amended to specify that this threshold applies to donations per year, and not to single donations. Additionally, in line with the recommendation above, this threshold could be lowered — for instance, to €1,000.

- Automatically publish due diligence information for all donations by legal persons. The Commission’s proposal request European parties to carry out due diligence measures for donations above €3,000; however, this information should only be reported upon the APPF’s request. Since European parties are required an extra effort to properly identify donors, this information should in all cases be reported by European parties to the APPF and published by the APPF alongside donations, in line with their respective reporting modalities.9

- Provide contextual and visual information on financial data. Finally, this entire analysis exercise by European Democracy Consulting aims at palliating the absence of visibility and readability for the information published by the APPF. While publishing this information in open data format will be useful for scrutiny by the press and researchers, it will not do anything for citizens visiting the APPF’s website. We therefore reiterate that, in order to provide actual transparency on the financing of European political parties, the APPF should be required to provide contextual and visual information, including tables, charts and other visualisation tools, to make this financial information clearly understandable to citizens. We are mindful of the work required for this goal and continue to advocate for an increase of the APPF’s staff and financial resources in order to properly carry out an extended mandate.

Overall, transparency measures under Regulation 1141/2014 have constituted an improvement. However, the continued difficulty to access this financial information and to properly makes sense of it underlines many of this Regulation’s shortcomings, eight years after its adoption and despite amendments in 2018 and 2019. Likewise, the current framework on the funding of European political parties has shown to make European parties overly dependent on public funding and to drastically limit their need for outreach to citizens. This year’s analysis confirms our previous findings and the circumscribed role played by small donations.

As the European Parliament and Council begin discussing the upcoming reform of Regulation 1141/2014, we call on both institutions to seize this opportunity and to make the funding of European parties and its transparency a cornerstone of this revision for the benefit of European citizens.

Annex

European Party Flashcards

Summary Table

- The PDF files for the 2018 and 2019 APPF reporting on donations and contributions are dated 9 and 10 February 2021, despite European parties being under the obligation to provide the APPF with this information at the latest six months following the end of the financial year — therefore 30 June 2019 and 30 June 2020. Likewise, the full information on 2020 donations and contributions was published in late February 2022.

- Sources:

– APPF webpage dedicated to donations and contributions: http://www.appf.europa.eu/appf/en/donations-and-contributions.html.

– Amounts of public funding for European parties provided by the European Parliament: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/contracts-and-grants/files/political-parties-and-foundations/european-political-parties/en-funding-amounts-parties-2022.pdf - We are mindful that the financial data in question covers the period 2018-2020 and that each European party’s number of MEPs changes noticeably from year to year — pre-2019 elections, post-2019 elections but pre-Brexit, and post-Brexit. For the calculation of values pro rata of each European party’s number of MEPs, we therefore use the number of MEPs for the year in question. For each year, the data on MEPs stems from figures used by the European Parliament to distribute public funding, and obtained by European Democracy Consulting by a request of access to documents.

- Data for European parties’ amount of reimbursable expenditure stems from figures used by the European Parliament to distribute public funding, and obtained by European Democracy Consulting by a request of access to documents.

- Or donations from natural persons between €1,500 and €3,000 for which the donor has consented to their identification.

- Donations from natural persons under €1,500 or between €1,500 and €3,000 for which the donor has not consented to their identification.

- In case of individuals making donations on behalf of someone else, there is simply no way to ascertain where the donation came from beyond the single individual who made the donation.

- Kindly note that, in this review, “private funding” is understood as the sum of private contributions and donations received by a European party. However, these may not be the sole sources of private funding received by European parties. As a result, it is possible that the indicate sum of “private funding” falls below the co-financing rate of Regulation 1141/2014.

- Donations above €12,000 and donations made within six months of European elections are reported and published on an expedited basis.