A recent conference organised by the Austro-French Centre for Rapprochement in Europe (CFA/ÖFZ) raised the issue of the EU’s East-West divide, as well as its forms and origins. One element missing from this discussion, however, was the potential presence of this divide within EU institutions, including in the choice of their location and leadership. The following review highlights not only a mere discrepancy in geographical representation, but a dramatic absence of entire European regions from the EU’s leadership. We propose a joint affirmative action programme by the European Commission and Council to start remedying this situation.

A note on political legitimacy

In his work on political legitimacy, Max Weber highlighted three main sources: traditional, charismatic and rational-legal. Belonging to this last category, modern democracies rest on the prerequisite that the governed, one way or another, are — or at the very least feel — represented by those in power.

In political systems with distinguishable demographic groups, the continued lack of representation of one or several of these groups can lead to frustration and popular dissatisfaction with the political system. Support for institutions may decrease and adherence to political decisions becomes uncertain.

Despite the creation of a common European citizenship through the Maastricht Treaty in 1992, national identities remain a strong identification factor in the European Union, and citizens by and large continue to associate with their co-nationals. As a result, a feeling of under-representation of the population of one or several Member States is not to be taken lightly, as it could severely undermine support for the EU’s institutions, values and policies, with dramatic consequences both within the population and, eventually, on the behaviour of national leaders, which in turn would impact EU governance.

Noting the rise of Eurosceptic feelings in Central and Eastern Europe, it is therefore useful and timely to have a look at the sociology of European leaders with a particular focus on their national citizenship.

Who are European leaders?

European Bodies

European bodies form a complex set-up that has expanded over time. Put simply, they comprise:

- Seven institutions listed in Article 13 of the Treaty on European Union: the European Parliament, the European Council, the Council of the European Union, the European Commission, the Court of Justice of the European Union, the European Central Bank, and the Court of Auditors;

- Advisory bodies also created by EU treaties, including the Committee of the Regions, the Economic and Social Committee, and the Political and Security Committee;

- Other bodies including the European Investment Bank, the European Investment Fund, the European Ombudsman, the European Data Protection Supervisor; and

- Over 40 agencies created by specific legislation, including “decentralised agencies” — such as the European Environment Agency, the European Food Safety Authority, Europol or Frontex — and “executive agencies” — such as the Executive Agency for Small and Medium-sized Enterprises or the European Research Council.

Modalities of representation

Beyond the civil servants manning these institutions are a number of individuals elected or appointed to decision-making positions. For collegial bodies, institutional rules often ensure some form of geographical representation. For instance, Members of the European Parliament are apportioned between Member States based roughly on population sizes, ranging from 6 to 96 per Member State. Likewise, the composition of the Committee of the Regions and the Economic and Social Committee are drawn up based on demography.

More often, however, European bodies support the principle of State equality, with each Member State assigned the same number of representatives. Each Member State has one Head of State or Government in the European Council, one minister per Council of the European Union (in each of the Council’s configuration), one Commissioner in the European Commission, one judge in the Court of Justice, and one member in the Court of Auditors.

In select cases, representation may be more complex. For instance, the Governing Council of the European Central Bank gathers one national governor per Member State of the Eurozone plus the six members of the ECB’s Executive Board, which are nominated by the Heads of State or Government of the Eurozone without explicit criteria for geographical representation. Members of the Executive Board hold permanent voting rights in the Governing Council, while national governors share voting rights according to a rotating system.

Another example is the Board of Directors of the European Investment Bank, which comprises 29 Directors — one per Member State and one for the European Commission; however, decisions require one third of members entitled to vote and representing at least 50% of the subscribed capital, with each Member State’s capital based on its economic weight within the European Union at the time of its accession.

Our focus

Beyond these modalities for citizen or State representation in collegial bodies are the highest leadership positions, where only one individual is elected or appointed — such as for positions of president or executive director. And this is where it becomes interesting to observe the geographical distribution of these positions in practice and whether all Member States or regions are fairly represented.

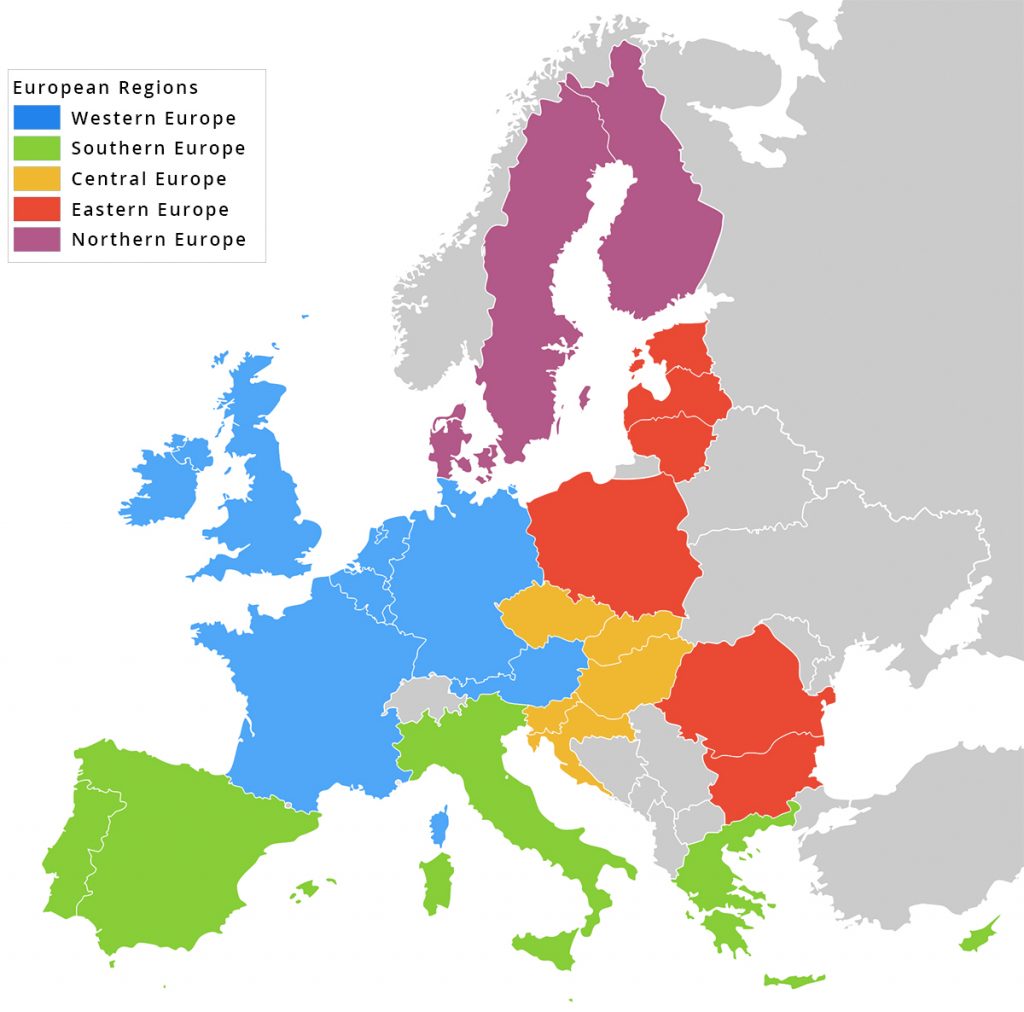

In order to review geographical representation, we choose the five regions of the map below. Their choice is based on historical, as well as cultural and economic criteria.1 Following the theme of the ÖFZ discussion, an even simpler East-West division could have gathered Western, Southern and Northern countries as “the West” and Central and Eastern European ones as “the East”, but the proposed breakdown is more precise.

Of course, the EU has grown over the years and a review dating back to 1958 would undoubtedly give a distorted image of geographical representation. As a result, where we consider a historical perspective, we start our review in 2004, following the “big bang” of EU enlargement, which saw ten countries join the Union. Reaching 25 members, the EU was close enough to its current membership.2

Of course, countries acceding in 2004 were unlikely to be represented right away at the highest echelons of European institutions. However, data from this period still captures useful information for Southern and Northern European nations having joined between the 70s and 90s.

From a more citizen-centric perspective, EU leadership positions of interest can be grouped in three categories:

- The EU’s “Top Jobs”: the Presidents of the European Commission, European Parliament, European Council and European Central Bank, as well as the High Representative of the European External Action Service (also Chair of the Political and Security Committee). These positions correspond roughly to the EU’s executive and legislative branches.

- The leaders of the judiciary and of the more recent institutional bodies, including the Presidents of the European Court of Justice,3 Court of Auditors, European Economic and Social Committee, Committee of the Regions and European Investment Bank, the European Ombudsman, the European Data Protection Supervisor, and the Chief Executive of the European Investment Fund; and

- The leaders of EU agencies, in particular their Executive Directors.

This categorisation is more pragmatic than academic, and the distinction between the “Top Jobs” and others is mainly based on their public exposure, the political nature of their role, and their joint nomination. As such, following the 2019 European election, the European Council nominated a package including four out of five top jobs, instead of solely submitting a name for the presidency of the European Commission.4

EU Agencies: location and leadership

The location of EU institutions has long been a source of contention between Member States, with two main opposing views. The first is that institutions should be spread across the EU in order to avoid undue centralisation, and so that all Member States may benefit equally from their presence on their territory.

Conversely, others argue that concerns of efficiency are more important, and favour the concentration of institutions, in order to facilitate their interactions and cut on travel and logistics costs. Admittedly, with the first institutions located in the first Member States, this argument clearly favours the set-up of more EU bodies in Western and Southern Europe.

Since the EU’s core institutions were mostly created before the major enlargement of the EU, all of them are located in founding Member States;5 thus, they are not particularly relevant for this review. Instead, let us focus on EU agencies.

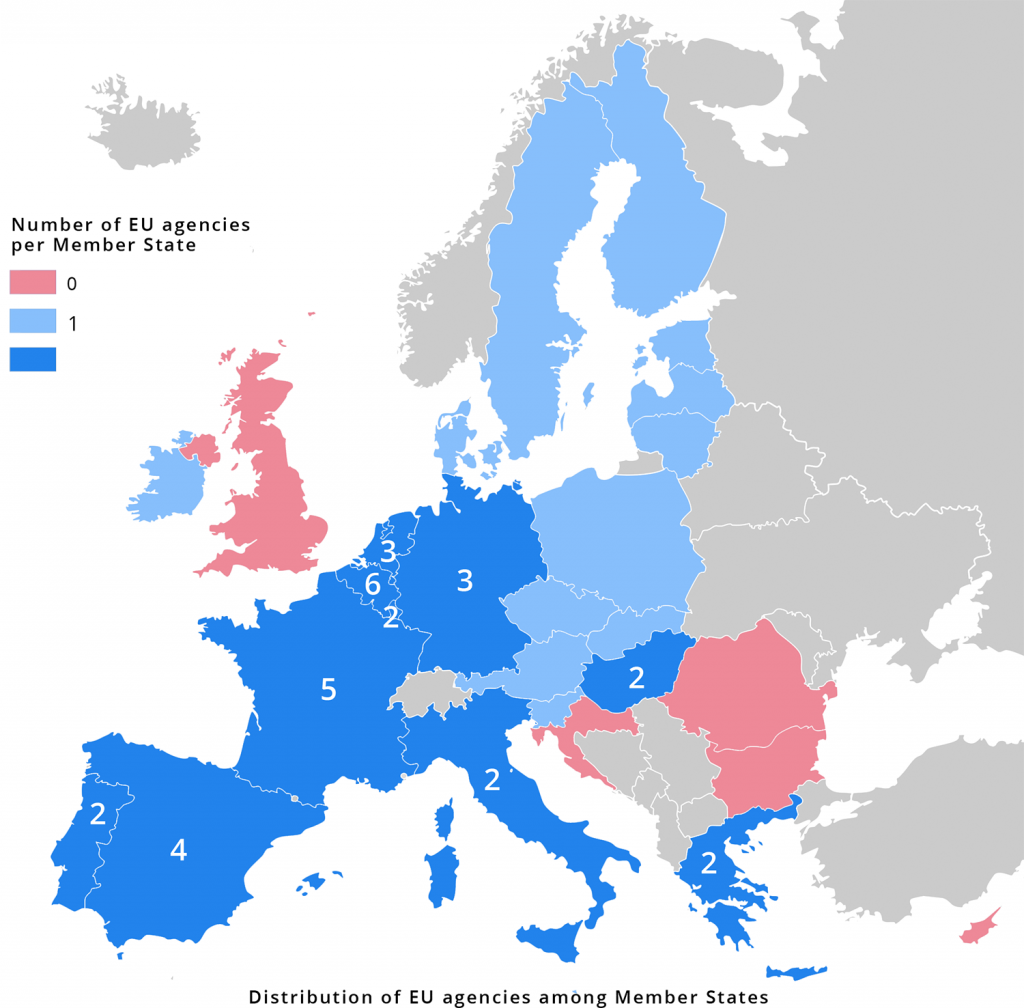

A map of the location of EU agencies first reveals a willingness to spread agencies across the continent. As such, almost all Member States (23 out of 28) are the host of at least one agency. Notable exceptions are the most recent Member States (Bulgaria, Romania and Croatia), Cyprus, and the United Kingdom following the recent move of agencies ahead of its planned exit of the Union.

A closer look reveals greater disparities, with Western and Southern Europe clearly reaping the lion’s share of agencies. For instance, Belgium, France and Spain respectively host 6, 5 and 4 agencies. Hungary is the only country outside of Western and Southern Europe to host more than one agency.

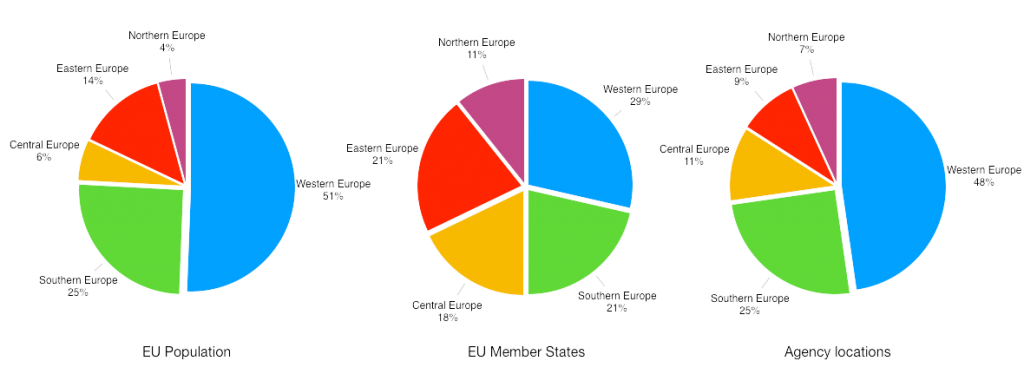

This begs the question of representation. As we have seen, representation can either be considered as proportionality to population size or as equality between Member States.

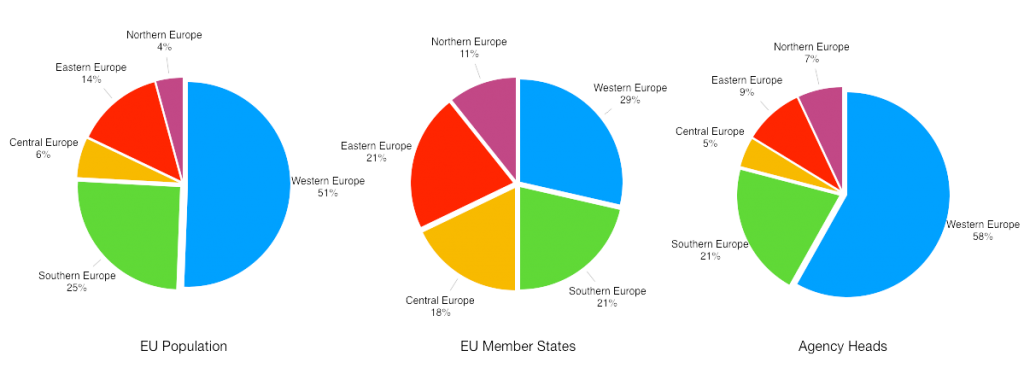

According to population size, Western and Southern Europe are proportionally represented, Central and Northern Europe are overrepresented, and Eastern Europe is under-represented. In terms of State equality, Western Europe is clearly over-represented to the detriment of all other regions, with Central and Eastern Europe bearing the brunt of the loss.

Of course, a number of agencies were created before EU enlargement to Central and Eastern European countries. However, even restricting our review to those created after 2004 shows disparities. Southern Europe loses in new agencies to Central and Eastern Europe but Northern and especially Western Europe maintain their share.

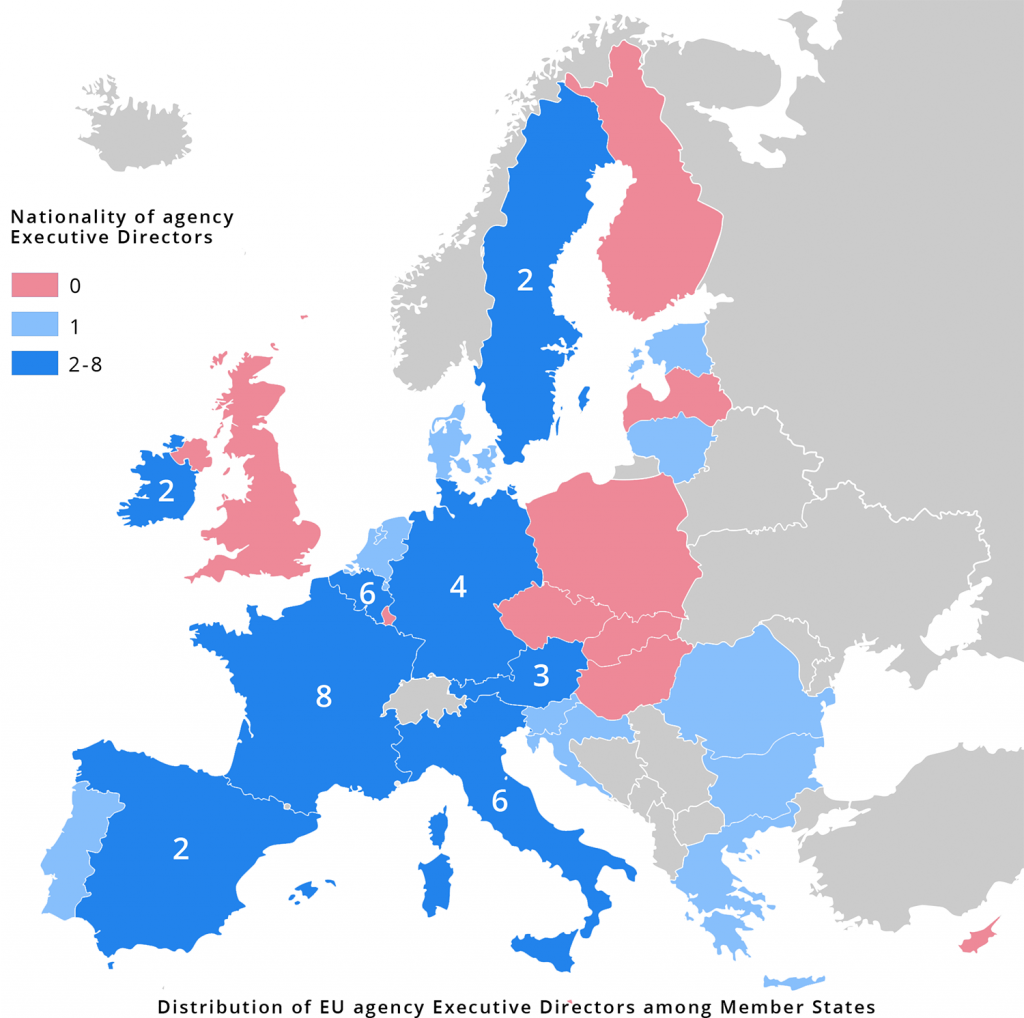

A more subtle criteria beyond an agency’s location is the nationality of its leader — usually an Executive Director, as these are the individuals guiding the agency’s policies and actions. Although these appointments are not political, the perception of continued lack of representation at the top of agencies can become a source of frustration for national leaders.

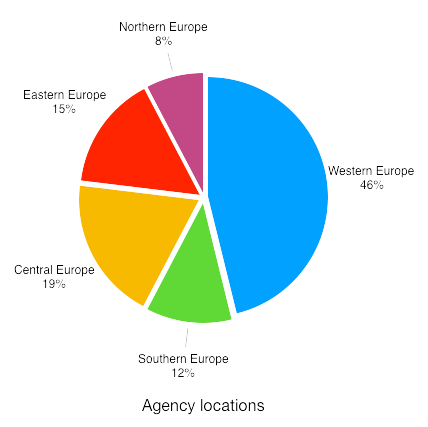

The periodic rotation of Executive Directors — unlike the rather fixed seat of an agency — should lead to a more distributed representation. However, figures for nationality in leadership prove even more tilted to Western and Southern Europe. Out of the 9 Member States not represented, 5 are in Central and Eastern Europe. France, Belgium and Italy top the ranking with 8, 6 and 6 leaders respectively, and no single country in the Eastern half of the EU has more than a single citizen leading an agency.

Overall, Western Europe alone captures almost 60% of these positions, and close to 80% together with Southern Europe. Western Europe goes beyond its population dominance and doubles its share in terms of State equality. Once again, Central and especially Eastern Europe are the clear losers of this distribution, making them less in command of the work of EU agencies.

Judiciary and more modern institutions

These positions are high level and carry a strong institutional weight — if slightly less political weight than the “Top Jobs”.

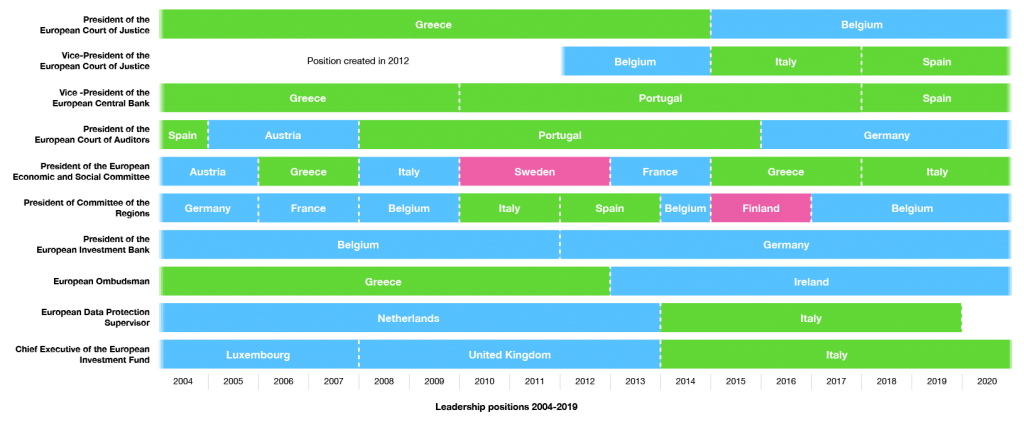

A notable criteria to consider is the duration of the position’s mandate. Some mandates — including that of the President of the European Court of Justice, the President of the European Investment Bank or the European Ombudsman — are particularly long, limiting turnover and the possibility of alternation, and, therefore, of geographical diversity. Others, such as the Presidents of the Economic and Social Committee or of the Committee of the Regions, change almost every other year.

In both cases, however, a review of the holders of these positions over the past 15 years shows a complete dominance of Western and Southern Europeans.

Strikingly, Central and Eastern Europeans are entirely absent from these leadership positions. Even Northern Europeans only managed two mandates for the 10 positions reviewed. In terms of mandate duration, these two mandate only cover about 3% of the total — leaving the remaining 97% in the hands of Western and Southern Europe.

Established respectively in 1952 and 1975, the Presidents of the European Court of Justice and of the Court of Auditors have come exclusively from Western or Southern Europe, with only a single exception each — a Dane in 1988-1994 and a Swede in 1999-2001.

Even the Committee of the Regions — established more recently, in 1994, but whose Presidents are elected for two-and-a-half-year mandates only — has only had a single non-Western or Southern European President, a Finn in 2015.

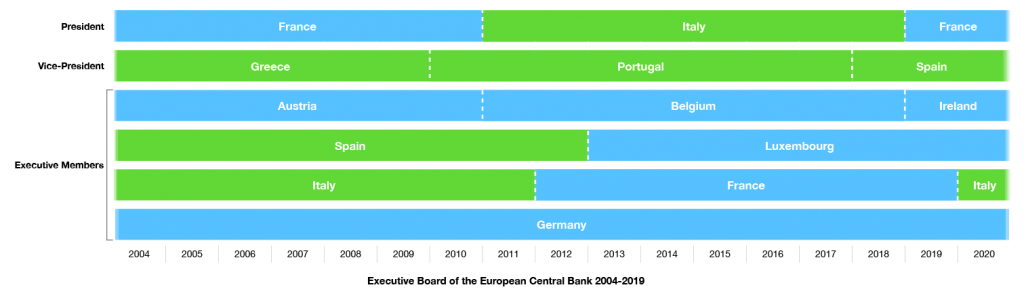

But the most revealing case is probably that the European Central Bank. The ECB administers monetary policy for the 19 countries the Eurozone, a core institutional prerogative. The Bank’s Executive Board is in charge of the implementation of monetary policy and of the management of the Bank, it can issue decisions to national central banks, and sits on the Governing Council where it contributes to the adoption of monetary policy — with permanent voting rights, while national governors follow a rotating system.

Despite these important powers, over the past fifteen years, not a single one of the twenty individuals who have sat on the Executive Board (6 at a time) has been either from Central, Eastern or Northern Europe.6 Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Slovakia, Croatia, Malta and Cyprus, all part of the Eurozone, have never had a single representative on the Bank’s Executive Board.

Leading the Union: the EU’s Top Jobs

Five positions embody the EU more than any others: the President of the Commission, the President of the European Parliament, the President of the European Council, the President of the European Central Bank, and the High Representative of the European External Action Service (HR/VP). For as much as citizens know European leaders, they are the faces and voices of our institutions.

The positions of President of the Commission and Parliament have existed, under one form or another, since the beginning of the European project. The Central Bank was set up in 1998, and the positions of President of the European Council and HR/VP were created in 2009 with the adoption of the Treaty of Lisbon.

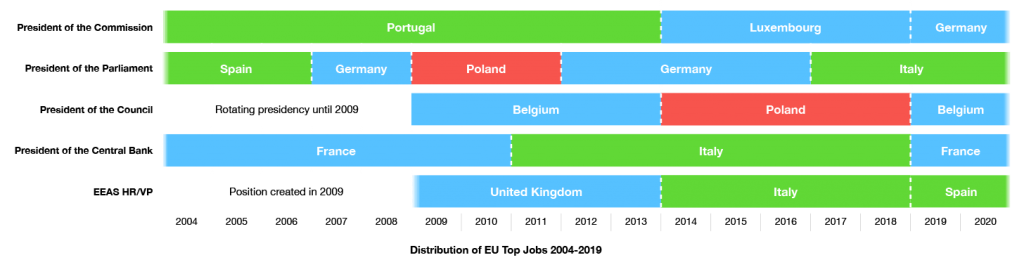

Following a similar trend as for other leadership positions, all but two of the office-holders of the past fifteen years have come from Western or Southern Europe. Jerzy Buzek and Donald Tusk, two former Polish Prime Ministers, were respectively President of the Parliament (2009-2012) and President of the European Council (2014-2019).

In a surprising decision, the “package” proposed by the European Council in July 2019 to fill the top jobs for the coming five years included no Central, Eastern or Northern European citizen. This is all the more surprising since a conscious effort was indeed made to provide some amount of representation: even though all nominees stem from Western and Southern Europe, all come from different countries and political affiliations.

Bulgarian Kristalina Georgieva, then-Chief Executive of the World Bank, was temporarily floated as a potential President of the European Central Bank as an overture to Central and Eastern Europe, but other political considerations must have proved more important than the inclusion of an Eastern European and her name was not retained.

Comparative representation

In 2004, ten countries joined the EU. These countries have now been Member States of the EU for over 15 years. It is enlightening to compare their current representation in the EU’s leadership to that, in 2004, of countries that had joined in 1995 (Austria, Finland, and Sweden; members for 9 years in 2004) and in 1986 (Spain and Portugal; members for 18 years in 2004).

In 2004, José Manuel Barroso of Portugal was nominated as President of the European Commission; he would continue on for another term in 2009. Josep Borrell of Spain was elected President of the European Parliament. The President of the Court of Auditors was Spanish (to be followed by an Austrian and a Portuguese), the President of the European Economic and Social Committee was Austrian, and the Executive Board of the European Central Bank comprised members from Austria and Spain.

Greece, which had joined in 1981, saw its citizens become President of the European Court of Justice, Vice-President of the European Central Bank, and European Ombudsman.

A full 15 years after joining the Union, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, Slovenia, Malta and Cyprus — let alone Bulgaria, Romania and Croatia, who joined respectively 12 and 6 years ago — have not held a single one of these positions.

Final thoughts on geographical representation

In the choice of locations and leaders for European institutions, the relative importance we give to the opposite tensions of efficiency and geographic representation depends on the goal we wish to reach.

In the early days of the European project, the limited number of Member States and the willingness to be amenable to the founding countries led core institutions to be distributed around. As the EU took on a greater role, the importance of efficiency become more prominent, solidifying the role of Brussels as the capital of EU institutions.

Starting mostly in the 90s and accelerating in the 2000s, the multiplication of EU agencies — with 26 out of 44 created in the past fifteen years — has allowed more flexibility, as technical bodies could more easily operate at a distance from Brussels, but also led each Member State to claim a share of the pie.

Surprisingly, nominations for leadership positions, which provide an opportunity for reshuffling every few years, have been more resistant to geographical diversity. Unlike Western and Southern Member States from the first rounds of enlargement, Central and Eastern European countries have not, fifteen years in, been successfully integrated in the EU’s leadership structure.

If we are to build an efficient EU leadership, it is true that geographical representation must be less important a criteria than the individual competence of institutional leaders. This is why precise geographic representation should not be blindly pursued.

However, it is less a certain lack of geographical balance than the complete absence of Central and Eastern European citizens in leadership positions that is striking from our review.

Indeed, the chronic under-representation of Central and Eastern Europeans at every single level of leadership, and especially in the EU’s Top Jobs, is sure to maintain a dissatisfaction in the EU’s least developed countries and a feeling that a system that does not play in their favour is continually led by others.7 As time passes, it becomes increasingly difficult to justify that no competent candidate can be found in these regions’ more than 100 million inhabitants.

The choice of the EU’s Top Jobs is done by the European Council and European Parliament. The appointment of Executive Directors of EU agencies is more complex but generally involves the agency’s management board and either the European Commission, Council or EEAS. With EEAS’ HR/VP answering to the Council and Commission, these last two institutions stand at the heart of the decision-making for almost every leadership positions.

In order to avoid the absence of entire regions from leadership positions, it is therefore essential for the European Council and European Commission to agree on a joint affirmative action policy aimed at remedying the current critical imbalance in leadership positions.

Only thus can we hope to prevent the development of “second-class citizen” feeling, and instead increase ownership of and support for the EU in Central and Eastern Europe.

~

Do you want concrete proposals to address this issue? European Democracy Consulting can help. Contact us for more.

1 The precise choice of the regions can be discussed. The most debatable element may be the positioning of Poland. As we will see, its inclusion in Central or Eastern Europe does not affect the conclusions of this review.^

2 On 1st May 2004, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, Slovenia, Malta and Cyprus joined the EU. Romania and Bulgaria followed suit on 1st January 2007, and Croatia on 1st July 2013.^

3 The Court of Justice of the European Union is the name of the EU’s overall judicial institution. It is composed of the European Court of Justice and of the General Court. In terms of leadership positions, we focus on the President of the European Court of Justice.^

4 The European Council failed to reach an agreement ahead of the European Parliament’s first session, where it elected its President. Short of that, it is likely that the European Council would have included this position in its package, even though the decision rests with the Parliament.^

5 The first enlargement took place in 1973 with the UK, Ireland and Denmark joining; two institutions were created at a later date. The European Court of Auditors was created shortly thereafter, in 1975, and located in Luxembourg. The European Central Bank was set up in 1998 and located in Germany.^

6 And, out of the 24 individuals who have ever sat on the Executive Board since the Bank’s creation in 1998, only one was neither Western nor Southern European. Sirkka Hämäläinen, from Finland, sat on the Council between 1998 and 2002.^

7 With the exception of Greece and Portugal, the 13 Member States having joined the EU in and after 2004 have the lowest GDP per capita (source: Eurostat, 2018). This situation has a wide range of factors but is likely to affect citizens’ view of the success and efficiency of the European Union.^

Pingback: EU Leadership Geographical Diversity Observatory – European Democracy Consulting